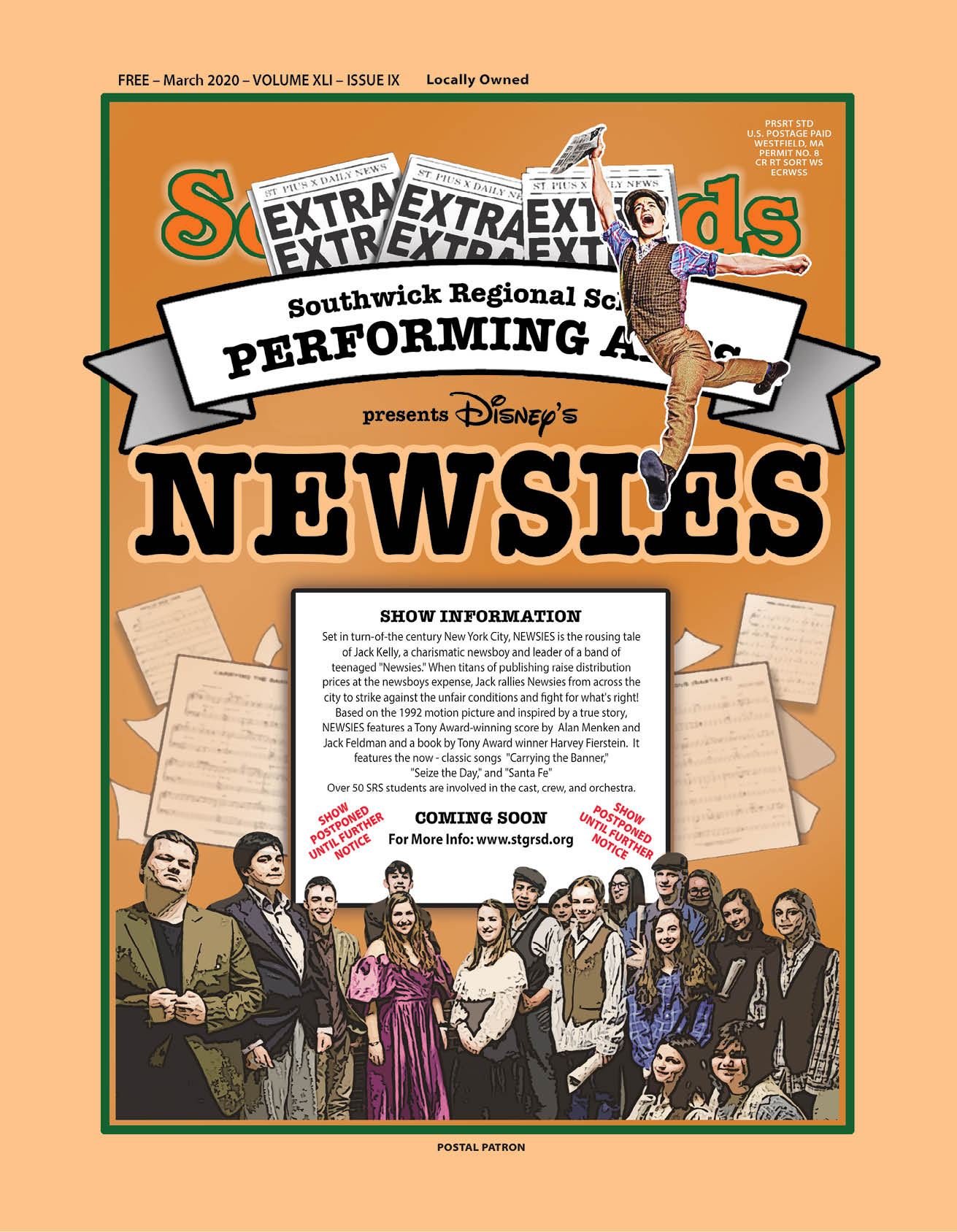

SOUTHWOODS MAGAZINE March 2020 PAGE 1

To the children of Southwick. I know right now things maybe a little confusing and maybe a little bit scary. But please know there have been many times that I have been scared and even a little confused, so you are not alone in those feelings. I just want you to know that all my Police Officers and I will be doing everything we can to keep you and you families read more

By Bernadette Gentry

The tops of the bare trees,

looking like the heads on lollipop

sticks reach their bare branches

to the sky.

There they give praise to their creator.

Like us they wait for the

Sun to warm them again

after Winter’s cold.

Before too long their buds

will open, and they will

be filled with color.

Later their leaves will

Appear and offer shad

and shelter to the birds.

And I think, we like they,

must wait patient

for beauty and hope to return

with early Spring dreams.

Image by Ulrike Leone pixabay.com

It seems hardly likely that a brutal murder scandal among the French nobility that rocked Europe and the United States in the 1840’s could have any thing to do with the little town of Southwick, but it does! It is also interesting to realize right now, when our coun-try is in the throes of its own sensational murder trial, that, even in the days before television, radio and the Trans Atlantic telegraph, such an event caused a media tizzy. Of course, the only recourse people had then was to grab up the newspapers hot off the presses to read the latest sordid details about the case.

The murder I speak of was that of the Duchesse de Praslin of Paris, and it occurred on the 18th of August, 1847. The Duc de Cho-iseul-Praslin of Paris, her husband, was arrested as the prime sus-pect. France was governed, at that time, by King Louis-Phillippe, but this case shed such a bad light on the behavior of the nobility that it contributed to the downfall of the monarchy in favor of a more republican system.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. In order to un-derstand the thread that connects this story to the little New England town of Southwick, we must delve into the past in more detail on both sides of the At-lantic.

Let us begin in Paris in 1841. Here, a young gov-erness by the name of Mademoiselle Henriette Desport-es left her position in London to return to her native France where she became the governess for the chil-dren of the Duc and Duchesse de Praslin. Both the Praslins were of the nobility, but it was the Duchesse, the daughter of the Marechal Sebastiani, who brought the wealth to the marriage that shored up the Duc’s ancestral estates.

While there seems to have been love between the husband and wife in the beginning and 9 children came from their union, the Duchesse was highly emotional and possessive, and the Duc’s love for her began to wain under the circumstances. She grew even more jealous and unstable and was hardly capable of caring for her chil-dren’s needs.

Then the Duc, who doted on his children and oversaw their

October 1995

upbringing with care, became dissatisfied with their present gov-erness, one whom his wife favored, however. He dismissed the governess in spite of his wife’s objections, and hired Mademoiselle Henriette Deluzy-Desportes in her place.

The new governess was neither extremely young nor beautiful, but she was an experienced, capable teacher for the Praslin children, and her character was impeccable. You can imagine, though, that an already awkward situation between the husband and wife grew worse as the children blossomed under Henriette’s care and the Duc’s gratitude.

In spite of Henriette’s efforts to sustain the children’s relation-ship with their mother, the Duchesse’s capricious, selfish behavior alienated her children. Her instability bordered on mental illness, and the Duc did not possess the strength of character to weather the emotional turmoil she caused in his family.

For 6 years Henriette stayed on as governess to the Praslins, and although she developed deep feelings for the children and the fa-ther, she never acted improperly in any way toward the Duc, nor did he toward her. Yet, because of his position, there were false accounts printed in the scandal sheets of the period that linked the attractive governess and the Duc in an illicit relationship and portrayed the wife as the helpless victim.

Finally, the Duchesse’s father, the Marechal, who still held the family purse strings, dismissed the blameless governess. The Duc had no choice but to go along with the decision in spite of its in-justice and the anguish it caused his young children. The Marechal promised that the Duchesse would write a letter of recommendation for Henriette so that she could obtain another governess position. However, months went by, and no longer came to Henriette. Several times the Duc brought his grieving children to see their old govern-ess at her temporary residence in a respectable but far from lavish Paris boarding house. During the last visit, Henriette’s landlady, who was also her friend, pressed the Duc for the letter of recom-mendation and he promised that Henriette would have it the next day if she called at his home at #55, Rue du Faibourg- Saint-Honore.

However, that night the Duchesse was brutally murdered, The Duc attributed the death to an unknown assailant who broke into the mansion but when his own valet led the police to the Duc’s blood-soaked clothing, ashes of burned letters in the grate, and the weapon, the evidence pointed overwhelmingly to the Duc as the true murderer. Soon the governess, Mademoiselle Henriette Deluzy-Desportes, was also taken into custody under suspicion of complic-ity in the crime.

She was incarcerated at the Conciergerie, the same stone prison where Marie Antoinette had languished on her last night alive. Al-though Henriette’s friends tried to obtain legal counsel for her, she refused, maintaining that her innocence would be her sole counsel.

The judges who examined her used every tactic to link her to the crime but to no avail--they could not sway her from her reasoned account of her life with the unhappily married Duc and Duchesse and her innocence of any wrongdoing. Though in a state of shock she defended herself eloquently and convincingly, and no evidence could be found against her.

The Duc obtained poi-son and died in prison of an appar-ent suicide only a week after his arrest. The public felt the Duc had gotten off too easily because he was a member of the House of Peers and a friend of the king. Sentiment al-ready against the monarchy now grew into public unrest. Although Henriette was cleared, the rabble sought to vent its wrath on her.

Now another thread is woven into our story, this one from across the ocean. It seems that a young minister from Stockbridge, Mas-sachusetts, one Henry Field, was traveling in Europe shortly after the Praslin murder trial; he had read the accounts in the papers and was greatly inspired by Mademoiselle Henriette Desportes’ remark-able self-defense. He managed to get an invitation to a party at the home of a prominent Paris minister where Henriette had been given refuge after her release. Field met Henriette, and in spite of herself Henriette was favorably impressed by this young, energetic Ameri-can who admired her so fervently.

Afterwards, Field went back to his travels, and presumably that was the end of the encounter. However, some time later, Henriette left France for America where she had obtained a teaching position at a fashionable girls’ school in New York City. It was only after she had arrived in New York that she learned that Henry Field recom-mended her to the headmistress of the school. Thus began a corre-

spondence and a friendship between Henriette and Henry.

Henriette was an excellent teacher,.but her wealthy pupils were difficult. When a few found out by chance that she was the govern-ess in the infamous Praslin murder case, it seemed that her new life would be destroyed by her past. Yet, with the headmistress’ per-mission, Henriette told the entire story to her students, and again, her eloquence and her innocence saved the day. She had no more problems at the school.

Meanwhile, the friendship between Henriette Desportes and Henry Field grew serious but before they could marry, she had to persuade his many brothers and sisters, his mother, and his step-father who was also a minister, that she was worthy of Henry. This accomplished, they became husband and wife and moved to West Springfield where Henry had taken a pastorate at the Congrega-tional Church there. From West Springfield it was only a short train ride to Henry’s beloved Stockbridge where his family lived, and it was even closer to the little farming community of Southwick, Mass. where Henry’s brother, Matthew Field and family resided. Thus the threads from France and America, now joined, become entangled with the larger story of the entire Field family and the birth of an amazing new technological breakthrough of the day. You see, Cyrus Field, another of Henry’s brothers, was the mastermind of the trans-atlantic telegraph cable from Europe to America. Cyrus Field spent a good portion of his life, energy, and wealth bringing that marvelous invention to fruition but not without enormous frustration, heart break and even the bankruptcy of his first company. Finally, after a number of failures, the two continents were linked by cable on July 29, 1860 and this was all chronicled in Henry Field’s book called His-tory of the Atlantic Telegraph.

Henry and Henriette eventually moved to New York City where he became the editor of The Evangelist, a religious newspaper of the day. Henriette tutored students from her former school to help make ends meet. The couple had a modest house in Grammercy Park which was, nevertheless, often filled with well-known writ-ers, artists, and thinkers of the day. Although she and Henry never had children of their own, they raised Clara Field, one of Matthew’s daughters, from the time she was two years old.

By Elaine Adele Aubrey

The author of this article recently returned from a World War II tour of Germany, the Czech Republic and Poland. Those countries offered a unique insight to a historical time period and are her observations of those countries.

The sign over the gate read ARBEIT MCHT FREI meaning WORK SETS YOU FREE. The prisoners walking through the gate were still trying to understand what was happening to them. The sign was a cruel trick to give them hope.

That was my introduction to the Auschwitz Con-centration Camp near Krakow, Poland, where 1.1 mil-lion men, women and children were killed during World War II.

I was a kid during WWII, and was unaware of its horrors. I didn’t understand the air raids and turning out our house lights. At the movies, newsreels with the latest battles didn’t seem real.

As an adult my interest began with a book The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich by William Shirer, which led me to countless other books. The war movies I saw put a picture to the words.

Over the years that interest continued because I was privi-leged to meet people connected to the War such as Brig. Gen. Paul W. Tibbets, the pilot who flew the B-29 named Enola Gay that dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. He was on a personal tour that included a visit to the New England Air Mu-seum in Windsor Locks, CT. Tibbets was accompanied by his bombardier Maj. Thomas W. Ferebee. At another event held at

One imagines that the Henry Fields made frequent visits back to Southwick so that Clara could see her parents, brothers, and sis-ters. At times they must have encountered Cyrus Field there because Matthew helped Cyrus do much of the planning for the cable in the summers at the Field house on College Highway in Southwick.

The Matthew Field home had been built by Enos Foote in 1803, and Matthew’s wife, Clarissa Laflin Field, had inherited it from her father. Unfortunately, the landmark two-story Colonial is no longer in existence. It burned down on May 25, 1928, at the time in the own-ership of Charles M. Arnold. The site was on the east side of College Highway between what is now the Congregational Church parson-age at 490 College Highway and the present day home and office of Dr. James Martinell at 498 College Highway.

Though the house is gone, those of you who were inspired by this account of Mademoiselle Henriette Deluzy-Desportes and Hen-ry Field and their affinity to Southwick, can read the story in more detail in the book, All This, and Heaven Too written by Henriette’s grand niece, Rachel Layman Field. The book was first published by Macmillan Company of New York in 1938 and is still in print as of the writing of this article. Warner Brothers even made it into a mov-ie starring Bette Davis. The Southwick Public Library will soon be adding this book to its permanent collection.

Copyright Elethea Goodkin 1995. Sources not mentioned in this text: Histori-cal Facts and Stories about Southwick, Maud Etta Gillett Davis, Southwick, 1951.

The Big E, I met Tibbets’ navigator Captain Theodore “Dutch” Van Kirk. On a return visit to the Air Museum, I met U. S. Navy veteran Michael Kuryla, a survivor of the U.S.S. Indianapolis. The Indy delivered the atomic bomb to Tinian Island. And on its return to base, the Indy was torpedoed and sunk.

As the years went by I took every opportunity to see any-thing WW II and that included historical sights like the WWII Memorial in D.C. and the Enola Gay on display at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center next door to Dulles Airport in Chantilly, VA. In London, I toured Churchill’s underground War Rooms.

Now my decades-long interest has brought me to Eastern Europe and Auschwitz with group of 28 touring Germany, the Czech Republic and Poland with an emphasis on World War II history.

After a 90-minute bus ride from our hotel and a long walk in the rain through a town cemetery, I saw the brick-walled Auschwitz and the metal archway that marked the entrance with the “Work Sets You Free” sign. Auschwitz had several di-visions but we visited only two – Auschwitz I which housed about 20,000 prisoners and Auschwitz II or Birkenau with 90,000 inmates.

We went up into one of the watch towers where the German guards had a bird’s eye view of the Camp. We did too as we looked out over the massive grounds and row after row of bar-racks, some with only foundations remaining. A Camp guide took us into the barracks. The wooden bunk beds were stacked to the ceiling and prisoners were crammed in side by side. The straw mattresses were flea and lice infected and there were few blankets in the poorly heated buildings. The hospital building isolated contagious prisoners but few ever reached it. Another building was for medical experiments and nearby we saw the restored gas chambers and crematoriums. We learned of the

unmarked mass graves and how the crematoriums’ chimneys scattered the ashes of the prisoners over the grounds. In plain sight of the horrors of the Camp was the commandant’s pa-latial home with an outside swimming pool for his wife and children.

After the War, additions to the Camp were added that in-clude a commemorative museum, a Jewish Center, a Synagogue and resource room. A separate room showed a film of the lib-eration of the Camp by the Russians. I could see the horror and disbelief in the prisoners faces.

In spite of the crowd of tourists, most of the time there was a stunned silence. Each room had a large glass-walled display area of what was taken from the victims – countless shoes, glasses, pieces of luggage, all kinds and sizes of prostheses and wheelchairs, hair, yes hair and other personal items. We saw it all up close, sometimes too close. As we walked from room to room there were quiet reactions to what we saw. I heard sobbing as I tried and failed to control my own tears. One young woman I saw was physically ill. The enormity of what we looked at took a toll on all of us.

Before leaving Krakow, we stopped at the site where Oskar Schindler’s factory once stood. He was a German factory own-

Above, A pile of glasses taken from Auschwitz victims. (By DIMS-FIKAS / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)

Facing Page, Entrance to Auschwitz (By Bibi595 - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org)

er who saved many Jews as depicted in the movie Schindler’s List, which tells the whole story. A museum stands there today but was closed the day we visited. A brass plaque honoring Schindler hangs outside the building.

Next stop, Warsaw, a city that was 85% destroyed by the Russians. It was painstakingly rebuilt and is a truly beautiful city. The Palace of Culture and Science is the tallest building and gives a fantastic view of the City. We visited Old Town, the Jewish Ghetto and Memorial and later spent some time at the Lazienki Park where Chopin is memorialized. In the nearby town square, Chopin’s music wafts through the air. It raised our spirits.

Thankfully, there were a number of lighter moments in the tour, like the visit to the Wieliczka Salt Mine. Check the web site for the incredible photos. This salt mine, 1,073 feet deep and 178 miles long, produced table salt until 2007. Now a mu-seum, it houses dozens of statues, chapels, a cathedral and un-derground lake all carved out of rock salt by the miners who considered it a great privilege to work there. To enter the mine, we walked down a spiral staircase with 378 wooden steps.

“Not to worry”, our guide said, “To return to the surface we have an elevator.”

During the war, the Germans used the mine for various in-dustries.

Wonderful food and very friendly people made it difficult to leave Poland but Berlin was calling so we headed there by train. The six and a half hour ride was in comfortable seats in closed compartments like in the movies, so now I’m looking for Hercule Poirot. Free coffee and water was available and there was a dining car that offered a buffet, not free.

......to be continued

Part Two

By Ross Haseltine

The Road King is packed and ready to go. Today we’re riding up to explore the abandoned Hudson-Chester Granite Quarry.

This place is cool! It’s almost as if work stopped one day and the workers never came back.

Littered about the landscape are a couple old trucks (pos-sibly a 1940s compressor truck and a haul truck), tanks, the ru-

ins of an electrical generator shed (probably purchased from Sears, Roebuck and Co.), old winches and hoists, rusty cables, old engines, and of course, the water filled quarry.

Some sources date the quarry back to the 1850s, but it is be-lieved to have started in 1880-81. However, it wasn’t until 1891 that the Hudson-Chester Granite Company was organized and although the quarry is in Becket, the granite, which was primarily used in monuments, became known as Chester gran-ite. Rough cut stone was shipped right from the quarry while the remaining product was shipped from cutting and polish-ing sheds located in nearby Chester, MA, and Hudson, NY.

The quality of granite coming out of the quarry was said to be “superior.” The same year the company was founded, they were looking to hire an additional 45 men, on top of the rough-ly 80 they already had. They needed the extra men to help fulfill a government contract to provide 50,000-cubic feet of dressed building stone for the arsenal at West Point. They also started construction on a large home to help house 100 workers.

By 1892, the company was looking to bring their work-force to 200 - just in quarrymen alone. That’s not counting the 20-horse teams who were hauling stone two or three miles from the quarry to the mill which was running day and night during this time.

When granite workers in New York went on strike a tele-gram was sent. It read: “send fifty (granite) cutters; no strike here; good stock and good work” - signed by E. C. Howley, sec-retary of the Hudson-Chester Granite Co. (1892).

The company experienced lots of growth and success, but it had its fair share of setbacks too.

1893 was especially hard. First, the company’s polishing and sawmill and their engine house burned to the ground on February 25th. Then in May, concerns over wages prompted workers in the Granite Cutters’ Union to strike.

The company was spending a lot of money transporting stone by horse. In September of 1895, Becket taxpayers declined

to fund a railroad spur to the quarry by voting down a pro-posal put forth by the company. But the company didn’t give up and the rail line opened in 1898.

On January 11, 1899 water pipes froze forcing a temporary closure until the burst pipes were repaired.

In September of that same year, people from all over trav-eled to the quarry to see what was described as a “monster block of granite.” The blasted rock contained no blemishes. Weighing 4,284,000-pounds, it measured 48-feet long, 42-feet wide and 12.5-ft thick.

Another dispute about wages plus the adherence to an eight-hour workday caused the company to shutter the quarry in 1904, thus putting all men out-of-work for a brief time.

The 14-year old, 300-ft. southern pine trestle, spanning Blandford Road along the rail line which lead to the quarry caught fire on July 6, 1912. It burned for about two-hours before crashing down onto the road below. Officials believe a spark from a locomotive caused the fire.

The company’s polishing and cutting plant was leased to the newly formed Chester Granite & Polishing Works in 1910 with the company signing a 10-year lease which started on April 1st.

Both companies were sued when a boy was blinded after a dynamite cap in a trashcan exploded on February 26, 1916. The court found in favor of the company.

Some sources say the quarry operated into the 1960s but it is believed that the company abruptly abandoned it in 1945-46.

DANGEROUS WORK

A 23-year old worker died in a freak accident at the quarry on July 16, 1901. He was attempting to lift a stone with an iron bar when the stone gave way. Another worker caught him as he was falling but the bar pierced his chest slightly above his heart and he died moments later.

A worker suffered a large gash from his right ear to his eye and another to his mouth while attempting to pry a large block of granite on June 10, 1909. He required 12-stitches.

On October 13, 1914, a 32-year-old worker, on the job about a week, fell. Hitting the bottom of the quarry he died instantly.

Resources for the Coronavirus

Prepare your

Family

Business & Employees

.

Community & Faith Based

.

Symptoms

Older Adults &

Medical Conditions

Schools & Childcare

.

Travel

How to protect yourself

If you think you are sick

To the children of Southwick. I know right now things maybe a little confusing and maybe a little bit scary. But please know there have been many times that I have been scared and even a little confused, so you are not alone in those feelings. I just want you to know that all my Police Officers and I will be doing everything we can to keep you and you families safe. A friend of mine Eeyore from Winnie-the-Pooh once said to me “A little consideration, a little thought for others makes all the difference." So please be considerate to your brothers, sisters, parents and all others. Just remember You are braver than you believe, stronger than you seem, and smarter than you think.

A big hug to all of you from Chief Bishop

------------------------------

To the elderly of Southwick, this is your Chief of Police Kevin Bishop. First of all, I would like each and every one of you to know that you are all in my daily thoughts and prayers as this horrible virus seems to affect our elders the most...

Now, I am asking you for your help and support during this dark time that has presented itself amongst us. I am asking all of you to reach out to family, friends and any others and to share stories and words of encouragement. I ask this because it is your generation that has had to endure so many challenges and hard times before and have always risen above and beyond and made it through. Others, from generations after yours have never had to face a dark, difficult challenge such as the one before us today and need some reassurance we will survive this one as well.

I am sorry to place this request on your shoulders but I know you all have the will and strength to help as you have proven so many times before. God Bless you, stay safe and stay healthy.

With much respect and admiration,

Police Chief Bishop

------------------------------

To the community of Southwick Massachusetts, I am writing to you now, not as your Police Chief but as a member of this community, as are you. I was Born and raised in Southwick and have resided here my entire life. I share this with you so that you know my concern for all of you to be genuine and true. I, like yourselves, am at times having feelings of anxiety and uncertainty but, I have full faith in the human spirit and humanity of the people of this community.

I have no doubt we will make it through this dark, difficult time and we will do it with patience, concern and compassion for each other. I firmly believe when these challenging times are behind us, we will once again stand tall with our heads held high and be proud we did not lower our standards and regards because of the uncertainty that forced upon us.

I am requesting one thing from all of you, and that is to PLEASE heed the recommendations of our healthcare professionals and to PLEASE, practice all safeguards that have been put into place, and of course, as much social distancing as possible. I ask this not for myself but for all of you, all of our healthcare professionals, fire/EMS workers, police officers and on a very personal level, for my daughter who is a paramedic and on the front lines, who are working so hard and sacrificing so much to keep all of us healthy and safe..

Please take these precautions seriously so you and your loved ones remain healthy and safe, and so that all of our health care workers and first responders may come home safely when this is over.

Personally, I have never been one to worry about the future, however, because of my position as Chief of Police, I now have the safety and well-being of so many others to think of, I must now, “ Plan for the worst, and pray for the best”, and that is just what my officers and I are going to do to ensure the safety of this community!

We are here to support, serve and protect you and we ask for your patience and cooperation in the days ahead.

Stay Safe, Stay Healthy, & God Bless all of you,

Chief Kevin A. Bishop

By Jim Putnam

Note: This is written as a story of how I imagine it might have been, based on the few facts that are known. It is not intended as a work of “pure history.” JNP

Imagine being one of the pioneering residents of what was then known as the “Southerdly Part” of Westfield in the 1760s…

You have established a farm somewhere near what are now Bugbee, Klaus Anderson and College Highway. It’s 6 miles to the meeting house in downtown Westfield to attend church and town meeting. There’s a dirt path north to Westfield by which you can travel by foot, horse or a horse and wagon. In ideal conditions, you might travel 3 to 4 miles an hour with a team of horses, and likely slower with oxen. When that path is muddy from recent rains or spring thaw, you stay home. You can’t risk the safety of your draft animals upon which you rely for your farming livelihood. In the winter, snow, ice and the cold make a round trip to Westfield even more difficult.

The more established you and your neighbors become in the “Southerdly Part”, the less you feel like full-fledged Westfield citizens. You sometimes miss Town Meeting because of travel challenges and it is impractical for you to be a Westfield town official. Town decisions get made, but you don’t feel like an equal participant. You pay the same tax rate, but don’t feel like you get your fair share of benefits. Perhaps when you do attend Town Meeting, some of the Westfield folks tease you and your Southerdly neighbors…

When you gather with your Southerdly neighbors (perhaps

over some hard cider or beer!), the conversation increasingly turns to this frustration. As the energy builds, someone boldly proposes “Let’s petition Boston for our own district”. Probably a chorus of voices erupts, some in favor and others not yet sure. Every time this idea is subsequently discussed, however, the voices of those in favor gain strength.

Petitioning required much greater commitment back then. Today we might sign a petition for some good cause and think no more about it. Back then it meant “putting your money where your mouth is.” Those who petitioned would be pledg-ing to jointly pay for “the settling of a learned orthodox min-ister” and “building and compleating a Meeting House for the worship of God.” For these relatively new residents with large families working hard to get farms and homes established, it’s a big financial commitment.

On March 15, 1765, the residents petition the General Court (Massachusetts Colonial Legislature) in Boston to be set off from the town of Westfield. (facing page.) And then, nothing happens.

The agitation likely continued. On May 22, 1769 another similar petition was sent to Boston. This time it was approved, the boundary with Westfield was established, the name “South-wick” was designated and a Charter effective November 7, 1770 was forthcoming.

A wonderful, vibrant American community was officially born: Southwick, Massachusetts.

Source: Historical Facts and Stories about Southwick, Maude Gillett Davis. Copies available for purchase through the Southwick Histori-cal Society.

The Founding OF Southwick

The Webb House. This dwelling was built about 1740, probably by John Root, one of the original settlers of the town. From “Images of America Around Southwick” by the Southwick Historical Society, Inc. Arcadia Publishing, 1997.

ORIGINAL PETITION FOR SEPARATION

The original petition, dated March 15, 1765, came into my possession on June 17, 1950, having been stowed away with some old family records. It is written in black ink, was very legible and is as follows:

“We the subscribers living in the Southerdly part of Westfield in the county of Hampshire - Being desirous to be set off a District from the town of Westfield and for the encouragement and promotion of the same and in consideration of our advantage do jointly and sever-aly promise to advance our equal part and proportion of money according to our respective interests for car-rying on a Prayer to the General Court for the purpose aforesaid and all charges accuring therefrom and also we further for the considerations aforesaid jointly and severally promise to fulfill our equal part and propor-tion advancing money according to our respective inter-ests for the settling a learned orthodox minister and for the building and compleating a Meeting House for the worship of God in said Southerly part and pay the same money unto the committee there chosen for the purpose of aforesaid for the use and benefit of the premises -viz - to Samuel Fowler, Benjamin Loomis, Joseph Moore, Daniel Olds, Noah Loomis, Matthew Laflin and Moses Noble - for witnesses thereof we there - unto severally subscribe our names -15th of March, 1765.”

Samuel Fowler

Aaron Granger

Joseph Moore

Abner Graves

Benjamin A. Loomis

David Wilcocks

Daniel Olds

Isaac Gillet

Matthew Laflin

Shadrick Moore

Noah Loomis

Amon Holcomb

Levi Root

Elijah Holcomb

William Moore

Micah Miller

Levi Tremble

Dames Moore

Jonah Stiles

Samuel Hare

Moses Nobel

Samuel Olds

James Smith

Ebenezer White

Samuel Johnson

Gideon Root

Gad Strong

James Stevenson

Abner Fowler

Silas Fowler

Nathan Warner

George Granger

James Campbell

Joseph Hide

Sampson French

Samuel Haines

Reuben Noble

Nehemiah Loomis

James Nelson

Rufus Stevens

Ephraim Griffin

Isaac Moor

David Kellog

Moses Wright

Moses Root

Giles Moor

Aphel Graves

Solomon Stevens

Isaac Nelson

Adanujak Burr

Ephraim Noble

Roger Root

By Sue Dutch

In early March, the north winds bring

Frost that makes us long for Spring.

The Arctic air so cold it leaves

Icy spikes on houses’ eaves.

All through March the days grow longer

While the sun grows ever stronger.

When southern winds at last arrive

Earth’s latent life starts to revive.

First crocuses begin to grow.

They force their buds right through the snow.

When they bloom and song birds sing

We’ll know that Winter’s turned to Spring.

To include your event, please send information by the 20th of the month. We will print as many listings as space allows. Our usual publication date is within the first week of the month. Send to: Southwoods Bulletin Board, Southwoods Magazine, P.O. Box 1106, Southwick, MA 01077, Fax: (413) 569-5325 or email us at magazine@southwoods.info.

HOLY TRINITY

Holy Name Society

Annual Breakfast

THE FAMOUS HOLY NAME BREAKFAST IS BACK. Join us on Sunday March 29th from 7:30am to 11:30am at the parish center for an all you can eat breakfast. The tickets are $8.00 (kids 12 and un-der are free!) Tickets can be purchased at Masses, at the parish office, from Holy Name members or at the door.

Southwick American Legion

Monthly Spaghetti Dinners

Southwick American Legion Post 338 will hold their monthly Spaghetti Dinner for March on Wednesday March 18th. Proceeds will benefit Post 338. The monthly Spaghetti Dinner for April will be held on Wednesday April 15th. Proceeds will benefit the Children and Youth.

Dinners will be held from 5:30-7pm and meals will include Meals will include: Spaghetti, Meatballs, Salad, Bread, Desert & Drink. Veterans and Children $5, every-one else $7. The American Legion is located at 46 Powdermill Road in Southwick.

Friends of the Southwick Senior Center

Seeking Tag Sale Participants, Crafters, and Vendors

On Saturday May 2, the Friends of the Southwick Senior Center will hold their outside “space only” sale on the grounds of the Southwick Town Hall from 9-2 (set-up starting at 8am). You can sell items you found during your spring cleaning or use this as an opportunity to sell crafts or other items. Spac-es are approximately 10’x10’ and the cost is $15.00 per space. Vendors supply their own tables, chairs and, if desired, canopy tents. Spaces should be reserved in advance. The sale will be promoted through local signs, press releases, and an ad in local newspapers. Refreshments will be available.

To reserve space: send name, contact information and payment (check made payable to Southwick Seniors,Inc.) to Southwick Seniors,Inc., PO Box 263, Southwick, MA 01077 - all reservations must be received by April 24. No refunds for can-cellations or for no shows. Call Joyce Bannish 569-3232 with any questions.

Holy Trinity

Rosary Society Annual

Bake & Food Sale with Raffle

The Rosary Society of Holy Trinity Church, Westfield, will be holding their fundraiser, a bake and food sale and great raffle in the Parish Center, 331 Elm St., Westfield on Saturday, April 4th from 3 to 5:30 pm and Sunday, April 5 from 7:30 am to 12 noon. We will have delicious home-made cakes, cookies, pies, candy and other desserts and rye breads & babka from Bob’s Bakery just in time for Easter. Homemade chicken, Corn chowder, golumbki soups and homemade kapusta will be sold in containers. Our Giant Raffle will include gift certificates, gift baskets and other great prizes for all ages. We hope to see YOU there!

Southwick 250

2020 Events

To commemorate the 250th anniversary of Southwick’s incor-poration in November 1770, an extensive lineup of community events is proposed.

March 14th - Southwick Pub Crawl

March 26th - Presentation: The Congamuck Indians of the Southwick Area

Apr. 16th - Catered Dinner: Over the Hills & Far Away Camp Music

May 2nd - Step into Spring Southwick 5k & Wellness Fair

June 13th - Adult Bus Tour: The History & Geography of Southwick

July 4th - Citizens Restoring Congamond Boat Parade

July 18th - One Call Away Motorcycle Ride, Family Fair, South-wick Civic Fund Firework’s

August 15th & 16th - Revolutionary War Encampment

September 24th - Presentation: Southwick 250 Plymouth 400 - in the Footsteps of Pilgrims

September 26th - Autumn Pumpkin Festival

October 9-12th - Southwick Reunion Weekends

October 11th - Southwick 250 Grand Parade

October 18th - Sarah the Fiddler

October 24th - Walk with Southwick Spirits

November 7th - Taste of Southwick Gala

November 8th - Presentation: Paddy on the Railroad & John Boyle of Southwick

Westfield Farmer’s Market

Seeking Vendors and Musicians

The Market Committee is seeking to expand the market to add a larger number of farms and variety of vendors, and is now accepting applications from vendors for the 2020 season. Subject to Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources regula-tions governing all farmers’ markets in the Commonwealth, the Westfield Farmers’ Market will accept locally grown produce and items made from local agricultural products. Musicians, crafters and vendors are encouraged to apply by contacting the Market Committee by leaving a voice message at 413 562-5461 ext. 101, email at farmersmarketwestfield@gmail.com, or down-loading information and applications from the Market website www.westfieldfarmersmarket.net.

Southwick-Tolland-Granville

Kindergarten Screening

The Southwick-Tolland-Granville Regional School District Kindergarten Screening for the 2020-2021 school year will be held on Thursday, May 7th and Friday, May 8th, 2020 at Wood-land School for Southwick, Tolland and Granville residents. In order to be eligible for Kindergarten, a child must be five years old on or before September 1, 2020. There will be no exceptions to this policy. Parents having an eligible child should come to the Woodland School Office at 80 Powder Mill Road, South-wick, MA to pick up an enrollment packet between now and April 27th. Open enrollment hours are 9:15 A.M. to 2:45 P.M. Return ALL information to the Woodland School Office. An ap-pointment will be made for you at that time to attend the screen-ing (May 7th or May 8th) to complete the registration process. Please call Woodland School at 569-6598 with questions

Dine Out for the Friends of the Westfield Athenaeum!

Join us on Tuesday, March 24, for a Dine-Out event at Tuck-er’s Restaurant in Southwick! Tucker’s will donate 10 percent of all food and soft drink sales (dine-in and take-out) during lunch (11:30-2:30) and dinner (4:30-8:30) to the Friends of the Westfield Athenae-um. No coupon required, just enjoy a lovely meal and know that you are sup-porting a contribution to the Friends! All proceeds support the programs and services of the Westfield Athenaeum.

Southwick 250 &

Southwick Historical Society, Inc

CONGAMUCK

INDIANS OF SOUTHWICK

Who were the Congamucks? Where did they live? Where did they come from? Where did they go? Presented by Joseph Carvalho III Thursday March 26, 2020 at 7:00 p.m. Town Hall Auditorium D0NATIONS ACCEPTED – ALL WELCOME Re-freshments will be served. Join us as we create history!

Citizens Restoring Congamond

SAVE OUR LAKES!

Prevent lake closure from toxic bacteria this summer! We need your vote Monday, March 23rd at 6:30 pm at the High School Auditorium in order to allow the Community Preserva-tion Commission to fund an alum treatment and keep our lakes open. The full funding for this treatment is through the CPC and will NOT increase taxes! Please visit Congamond.org for more details.

Tops Club, Inc.

Weight Loss Support Meetings

TOPS will be holding it’s weekly meeting at St. Peter & St. Casimir Parish, 34 State Street Westfield Ma on Tuesdays start-ing with Weigh-Ins from 5:15 to 6:00pm followed by a short meeting from 6:10-7:00pm. New members get the first month free! If you are interested in losing weight try this program first.

TOPS (Take Off Pounds Sensibly) is the original nonprofit, noncommercial network of weight-loss support groups and wellness education organization.

COUNTRY PEDDLER

CLASSIFIEDS

GOODS & SERVICES

GOODS & SERVICES

traprock driveways built & repaired. Gravel, loam, fill deliveries. Tractor services, equipment moved, York Rake. Bill Armstrong Trucking. 413-357-6407.

DELREO HOME IMPROVEMENT for all your exterior home improvement needs, ROOFING, SIDING, WINDOWS, DOORS, DECKS & GUTTERS extensive references, fully licensed & insured in MA & CT. Call Gary Delcamp 413-569-3733

RECORDS WANTED BY COLLECTOR - Rock & Roll, Country, Jazz of the 50’s and 60’s All speeds. Fair prices paid. No quantity too small or too large. Jerry 860-668-5783 or G.Crane@cox.net

House for rent - Southwick, Ma Dutch Colonial 8 rooms, 3 beds, 2 bath, kitchen, living, dining, den, family room, 2 car garage. New Kitchen floor. No pets. Call 860-558-1077 before 2pm.

Grow fresh Shiitake Mushrooms - Pre-inoculated shiitake kits and logs available for the 2020 outdoor growing season. Also, now booking April timeslots for inoculate-your-own-log sessions in Granby CT. shiitake@cox.net or 860-593-2267 www.rmsgrowers.com

Personal Shopping - From fashion to groceries Heart of Gold shops for you. Specializing in disabilities. Contact Margaret Nicolai 413-563-0518