By Clifton (Jerry) Noble Sr.

January 1, Monday. Jerry Jr., born April 21, 1961 (there-fore 8 months and 9 days old) weighs 17 pounds 9 ounces. There’s no rain so I made five tenth-mile trips to bring 2 pails per trip. I am thankful for 20 rock steps up from the brook as they help to balance while climbing with a pail of water in each hand especially when there’s ice.

After dinner we took baby down to Eliza-beth’s parents in Westfield, so she could take bath and wash hair. I picked up my mother at Sarah Gillett old ladies home and brought her up to 8 Hawthorne Ave. so she could see baby and have a short visit. Baby creeps and was very good.

At home I made three more brook trips for water and put the 1962 registration sticker on my state car.

January 2, Tuesday. At Greenfield office. Gordy Parker and Dick Nelson came in to meet Al Parmenter and collect equipment for their new survey party. In his watch and jewelry shop my cousin, Lester Emerson, had me choose from two rings to replace the one Elizabeth acciden-tally flushed down the toilet. He is getting me an $82.50 diamond ring for $55.

January 3, Wednesday. At noon I got a rub-ber sheet at Zayers for baby’s crib. After getting 1962 calendars at Wilcox Insurance and Kneil Coal Co. I stopped briefly at SGH to see my mother. She was playing piano and asked me to play a few things for her.

January 4, Thursday. E is 36 today. I gave her birthday card and new ring before baby woke. I worked on state job diary while doing wash at Glen Launderette.

January 7, Sunday. Rev, Arthur E, Teale came to Montgomery Community Church from Granby, Connecticut. His wife Lillian came with him. My mother Hester helped with choir and enjoyed the sermon. We went home through Huntington and Russell because of ice. There was enough water from melting roof drips to heat for my bath.

January 8, Monday. Glen Biggam was in of-fice. I told him I saved article about him singing in operetta with broken foot a few years ago. He calls singing “controlled yelling.” Dr. Wonson told E she is spoiling baby, that he must have po-lio shot, and made a next-week appointment.

January 9, Tuesday. To save precious water, I used the outhouse across the road, heating it with the portable oil stove from the school-house. There was a dead mouse in the well so I made a pan skimmer with a ten-foot handle to reach down and scoop it out. State car had a flat tire from a break in side wall. Had to get it fixed promptly at P.O. Service Station as I was supposed to go to funeral of Al Murphy’s father, who was 87.

For a replacement at Northampton store-house I got the second bald tire that came off that same car a year ago January. It was put on in Westfield. I got coffee for guys working at river, and collected for “flower fund.” Louis Johnson took afternoon off to go to Deep River, Connecti-cut, to check on his mother who fell Christmas day. I visited my mother briefly at SGH. When I phoned Elizabeth she was making formula. She paid Jean Watson to do washing and go with her to Dr. Wonson’s while baby had his second polio shot. I got 7 Polaroid pictures together to have negatives made. Temperature was in low teens so started fire in wellhouse stove.

January 11, Thursday. Made 6 trips to brook for water.

January 12, Friday, Bessy Prout and Edith Robbins closed the Sarah Gillett’s sun parlor door while Hester was out there doing a puzzle. Matron Peterson gave them Hail Columbia be-cause the thermostat for the house is out there.

January 13, Saturday. I started wellhouse stove. Temperature was 2 above 0. I took Hester to Color Center on School Street for brushes and to Johnson’s Bookstore in Springfield for paints. Also got a calculus book for $2. Got clothes bas-ket, groceries and nipples. I put woodshed in order, got kindling and took pictures of baby. Waxed skis. Had wonderful time in sun on easy slopes of Barnes meadow. Bill Chadwick came while I was at laundry. He is Russell Assessor. I went to his house on Blandford Rd. to show him how to plot plans from bearings and distances shown on deeds.

January 14, Sunday. Hester helped choir with communion service. Sherry Jourdain did well with solo. I napped on couch while E and H chatted and baby bounced in chair. Atwaters took H home at 4:30 p.m.

January 17, Wednesday. My cold symptoms are gone. The refurbished A&P is open and their parcel pickup operates. Baby makes “Da Da,”and “Ma Ma” sounds.

January 18, Thursday. This afternoon God guided me to find Fiske’s party on Roosevelt Ave. in Springfield. E is being more careful with wa-ter so I may stop making icy trips to the brook.

January 19, Friday. Stopped at Uncle Ralph’s shop to pick up check books I left there Tuesday. He fixes mostly watches but just did first two clocks in ten years.

January 20, Saturday. Baby reached for beads on play pen first time. Am so thankful that God sent Monday’s rain to take care of wa-ter in our well.

January 21, Sunday. Up 6;30 a.m. Made beds. Ironed sheets, pillow slips, pants, two shirts, and sewed button on white shirt. Got today’s paper in Russell and took Hester to church. Rev. Ar-thur E. Teale is to be permanent minister. Did our accounts. My blind cousin, Flora Hallock phoned. The Ball house where she rooms on Lit-tleville Road is being taken for flood control, but she will go with the family wherever they go.

January 22, Monday. A&P has started giv-ing Plaid stamps.

January 23, Tuesday. I put baby in clothes basket during breakfast. I gave him a ride in it the other day. On the way through West Spring-field’s Park St. I picked up a copy of College Al-gebra at Library Book House, and got Harmony at Blodgetts in Springfield. Aliengena and Rap-isarda had their grade two appointments cut back to grade ones. E said baby pulled himself to standing position in clothes basket twice to-day. Dick Barker told me that June will be his last solo dance recital before getting married.

January 26, Friday. I got stopped in Hatfield when the gas pedal linkage on S216 came apart. Finally I got Joe Yablonsky to have car towed into Locust Street garage where Vic D’Lesko fixed it so I could continue to Greenfield. Mlecko and Gilbert have been laid off. Gilbert has four kids and a sick wife

January 27, Saturday. After finding nee-dle stuck in bedspread I mended shirt and E’s apron. After dinner I took baby pictures to Aunt Georgia. She has been baby-sitting at Llewelyn Drive while young Ralph and Martha attend Philadelphia paper convention. With her lame-ness she looked from kitchen down long hall to bathroom and told herself, “You better get going or it will be too late.” At home E said baby stood up by holding top rail of playpen, also how he got out of little chair and hid on her behind ot-toman.

January 28, Sunday. At home baby crept around living room. He obeys “No, No” pretty well when we don’t want him to touch some-thing.

January 29, Monday. On way up Norwich Hill I saw gas was very low so turned and coast-ed most of the way back to Crown Station in Huntington to fill tank.

January 31 Wednesday. Greenfield Recorder article mentions 50 more Public Works layoffs. I am grateful to have permanent appointment so can’t be laid off.

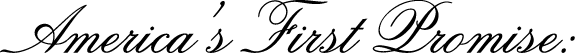

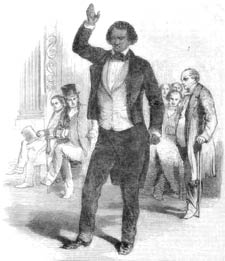

America began with a sentence that was far bigger than the country itself.

When the Declaration of Independence as-serted that “all men are created equal,” it was not describing the current reality. It was an-nouncing a proclamation of ambition for the forming country. In 1776 it applied to few, ex-cluded many, and yet, it changed the world.

That contradiction—equality declared but not all felt that truth—was America’s first great test to the new government experiment. Start-ing in a state of failure and through the efforts of many, it’s first world-changing success.

The founders knew they were doing some-thing unprecedented. They were not appeal-ing to ancient custom or divine authority. They were claiming that legitimacy flowed from the people themselves. Governments existed to protect rights, not grant them. That idea, radi-cal for its time, spread far beyond the thirteen colonies. Revolutions echoed it. Constitutions borrowed from it. Movements measured them-selves against it.

But inside the new nation, reality lagged be-hind rhetoric. Voting rights were narrow and were based on property ownership. Women were legally invisible in public life. Enslaved people lived and worked chained to their mas-ters in a country proclaiming liberty. Indig-enous nations were treated as obstacles rather than partners. The promise was written broad-ly; its application was painfully selective.

This gap wasn’t accidental. It was strategical-ly political. Thomas Jefferson, who held mixed views on slavery, calling it a “moral depravity” and a “hideous blot,” believing it harmful to both the enslaved and the enslavers, and contra-dictory to American ideals of liberty, described the dilemma as “holding the wolf by the ear,” unable to let go or safely hold on, balancing justice with self-preservation. Unity required compromise, and compromise meant postpon-ing justice. The founders chose survival of the experiment over immediate fulfillment of its ideals. History has judged that choice harshly—and rightly—but it’s also impossible to under-stand America without it.

Because once the promise existed on paper, it could be invoked by anyone.

That is the quiet genius of America’s first fail-ure. By declaring equality without enforcing it, the nation created a standard it could never fully escape. Every generation that followed re-turned to the same words and asked the same question: If this is true, why doesn’t it apply to us?

Abolitionists asked it. Suffragists asked it. Workers asked it. Civil rights leaders asked it. Each time, the country was forced to confront the distance between its ideals and its behavior. Reform movements did not need to invent new principles; they needed only to demand that the promise be kept honestly.

Progress, when it came, was uneven and incomplete. Rights expanded, stalled, and expanded again. Gains were often met with backlash. The promise moved forward not in a straight line, but through persistence. The im-portant thing is that the promise remained the reference point. America argued with itself us-ing its own founding language.

That argument still plays out most clearly at the local level. In towns founded in New Eng-land and beyond, democracy has always been practical before it was philosophical. Town meetings, school boards, volunteer committees, and local elections put the promise to work in everyday ways. Decisions are debated in per-son. Outcomes are imperfect. But participation itself becomes proof of belonging.

This is where the lofty words of 1776 find their footing in places where neighbors disagree and still show up. A place where civic life is not symbolic, but routine, where the promise feels less like a slogan and more like a responsibility.

At our 250th anniversary, it’s tempting to measure America by our current implementa-tion of such promises. But that misses the deep-er achievement. Few nations have written ideals so boldly, so early, and then allowed genera-tions to challenge them openly. Fewer still have survived the argument, descending back into authoritarian rule.

The promise of equality did not col-lapse under its contra-dictions. It endured because Americans kept insisting it mat-tered. The failure to deliver it immediate-ly did not nullify it; it activated it.

That is the uncomfortable outcome at the heart of the American experiment: the country works not because it gets everything right, but because it leaves itself open to correction. The promise is not self-executing. It depends on citizens willing to point out where reality falls short and push for belonging. The American experiment provides not unquestionable truths but clarity.

Our promise of equality gave something the world had not seen, a country brave enough to define itself by ideals it knew it had not yet earned but chosen specifically so it was inter-twined into the lives of its people and asked them to make it a reality. Two and a half centu-ries later, the promise is still debated. What out-wardly appears to be a weakness is its strength. That “We the People”, not a king, authoritarian or blessed few, continually redefine our coun-try. We learn from our mistakes, we chose who represents us by what is and isn’t working with our voices and votes. Nothing is unchangeable, nothing is unachievable. It is the work towards a better tomorrow; the diplomatic process of an ever-changing, ever bold, United States of America.

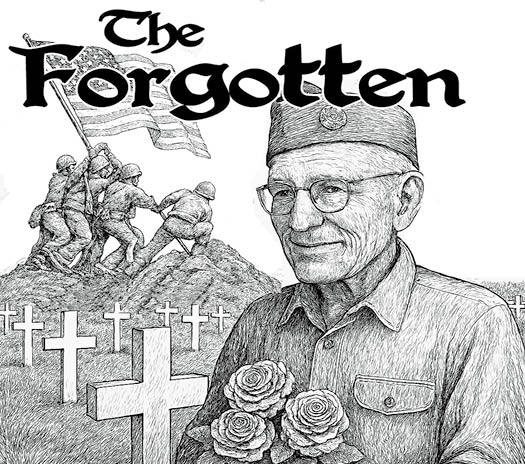

When yet a lad, long years ago, I knew a group of men.

It was the nineteen fifty’s , they were old even then!

They told of battles, far away, The Arragon, the Marne, and Suvla Bay.

They told of Flanders and the dead, where poppies grow today,

They keep a vigil in that place in eerie, mute display!

The horror of the trenches, and the sight of death’s decay.

Artillery laid bodies bare, and there was where they lay.

Now they are gone, I knew them well. They’ve no more tales to tell.

And even history can’t recall he blood, the bursting shell!

I remember further back, when I was just a tot,

Life magazine, an article not soon to be forgot.

The last Confederate drummer boy the last in all the world,

Had gone at last to meet the Lord, with stars and bars unfurled.

All we have left in memory are songs and history books

On faded, yellowed pages in places no one looks.

My my dad told tales of “The Great War” but peace was not to be.

But still men fought, and still men died, in seeking to be free.

And soon we gave them numbers, World War I and World War II.

But now we know that even then the fighting wasn’t through!

Now we try hard to recall and some try to forget,

The many names, now fading fast, much to our sad regret.

Corrigador, Battan, Berlin, the Battle of the bulge,

And countless other places where our heroes would indulge.

Who can forget their noble work, forget their noble task?

They raised the flag on Iwo Jima, What more could we ask?

Few now are left, a struggling few, of men now old and gray.

Lift high the torch they pass to you, bring their night into day!

And when, at last, the guns had ceased, with but a few years past,

The guns in North and South Korea made a stormy blast!

We saw another war begin, we saw more soldiers die.

We still have many thousand there, a truce these troops belie.

And then, in nineteen fifty-five we saw more war begin.

In the land of Viet Nam, a war we could not win.

And day by day, and year by year, we face each future fray.

And wonder what the future holds, and who will die today!

by Phil Pothier

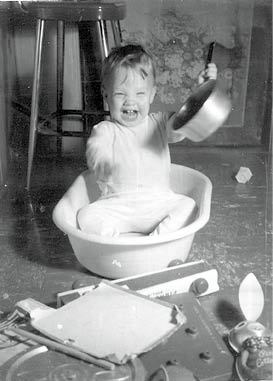

Jerry Jr., 8 months

January 1962

“I made 3 more brook tripsfor water”

January 2015

Emotional regulation is often de-scribed as a skill we’re sup- posed to have—something we master before emotions run high. But parenting doesn’t hap-pen in calm, controlled environments. It hap-pens when you’re tired, overstimulated, and juggling responsibilities while your child is hav-ing a hard moment.

For many parents, the challenge isn’t un-derstanding what emotional regulation is. It’s knowing how to access it in real time—without extra time, silence, or perfection.

That’s where micro-habits for emotional reg-ulation come in.

Micro-regulation isn’t about staying calm all the time or responding perfectly. It’s about building awareness and capacity through small, intentional actions that support your nervous system as life unfolds. These moments are brief, often subtle, and sometimes invisible to oth-ers—but when practiced consistently, they cre-ate meaningful change.

Reflective parenting emphasizes pausing, noticing emotions (both your child’s and your own), and responding with curiosity and com-passion rather than automatic reaction. As a Re-flective Parent, you don’t need more strategies to memorize. You need practices that fit into real moments, respect your nervous system, and leave room for imperfection—while supporting both self-regulation and co-regulation with your child.

The micro-regulation moments below are de-signed with that reality in mind. They are not meant to be followed perfectly or used all at once. Even choosing one to return to consistent-ly can gently shift how emotions move through your day.

1) Name It to Tame the Moment: Regulation begins with awareness. Quietly naming what you’re experiencing—“I feel rushed,” “My body feels tight”—helps reduce emotional intensity. Naming isn’t fixing; it’s orienting.

2) Soften Before You Speak: Your facial ex-pression sends powerful signals to both your nervous system and your child’s. Gently soften your jaw, brow, and eyes before responding. This small shift often changes the tone of an in-teraction without changing your message.

3) Let One Breath Lead: Instead of focusing on breathing techniques, try one slow exhale. Lon-ger exhales help your nervous system downshift naturally. One breath can interrupt reactivity.

4) Come Back to Your Body: When emotions rise, attention often moves into the head. Notice your feet on the floor or the surface supporting you. You don’t need calm—just presence.

5) Shrink the Moment: Stress grows when we think too far ahead. Ask yourself, “What do I need to do in the next five minutes?” You only need to manage this moment.

6) Choose a Pause Anchor: A pause anchor is a small, repeatable action—touching a bracelet, pressing your fingers together, placing a hand on your chest—that signals safety to your ner-vous system.

7) Lower the Volume, Keep the Boundary: Regulation often improves when emotional in-tensity decreases, even when boundaries stay firm. Slow your speech, lower your voice, and use fewer words.

8) Let Stress Move Through: Stress creates physical energy. Gentle movement—stretching, pacing, rolling your shoulders—helps the body complete the stress response.

9) Notice the Win You Almost Missed: Instead of asking, “Did I stay calm?” ask, “Where did I pause or recover more quickly than before?” Progress lives in noticing.

10) Say the Repair Out Loud: Children learn regulation by watching how adults recover. Simple repair—“I was overwhelmed earlier, and I took a breath”—teaches more than perfection ever could.

Micro-regulation moments aren’t about con-trolling emotions or getting it right every time. They’re about returning to yourself—again and again—in the middle of real life. Over time, these small habits create a rhythm of awareness, repair, and connection that children can feel and learn from.

You don’t need to practice all ten. Choose one moment to return to when things feel hard. Let it meet you where you are. Even the smallest pause can make room for something different to unfold.

Which micro-regulation moment stood out to you? Which might support you during your most challenging parenting moments this week? Small moments, practiced often, create lasting change.

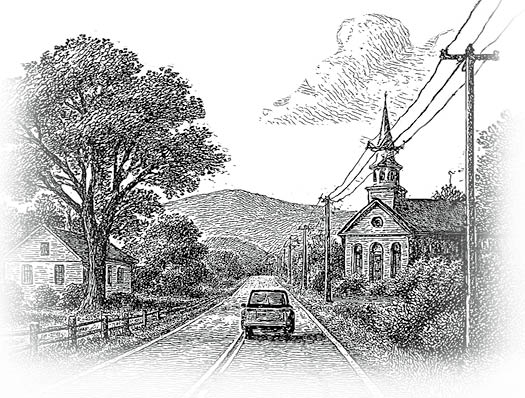

Long before it carried the dual shields of Route 10 and 202, College Highway, the road running through Southwick, Granby, Westfield, Northampton, and the surrounding towns served as a vital north–south corridor. It was a practical thing, worn into the earth by hooves, wagon wheels, and the steady insistence of people who needed to get somewhere. But the old-timers say the road had a character even then, a kind of quiet purpose, as if it understood it was meant to car-ry more than just freight.

In the early days, the land around it was a patchwork of farms. Cows grazed in low mead-ows, tobacco leaves dried in long barns, and the scent of cut timber drifted down from the hills. Wagons creaked along the road carrying milk, butter, and cheese toward the markets. Tobacco traveled south toward the cigar makers. Timber went north to the mills. Even blocks of ice, cut from Congamond Lakes in the deep of winter, were hauled along the same route, wrapped in sawdust and hope that it would last the jour-ney. The road learned the weight of work early.

When the mills rose along the rivers, the road changed its rhythm. It carried spools of thread, stacks of paper, crates of machined parts, and the footsteps of workers moving between towns. Some say you could tell the time of day by the sound of the traffic: the morning shuffle of la-borers, the midday clatter of delivery wagons, the evening drift of tired feet heading home. The road became a kind of pulse for the region, steady and dependable.

The name “College Highway” came later, and like most good names, it wasn’t chosen so much as it settled into place. The valley grew into a landscape of learning, dotted with acad-emies, seminaries, and colleges. People traveled the road for lectures, recitals, meetings, and the simple business of keeping knowledge moving. The road, already accustomed to carrying the work of hands, now carried the work of minds. Locals began calling it the college road in recog-nition that it was capped on both ends by Smith College in Northampton and Yale University in New Haven. It linked communities where education played a central civic role and tied together the region’s schools and students, the same way it tied together its farms and mills.

When the state finally put numbers to the highways, the old name stayed. Folks insisted on it. They said the road had earned it, and you don’t take a name away from something that’s carried so much for so long.

Even now, if you drive it at dawn, you can feel the layers beneath the pavement. The echo of wagon wheels. The hum of mill carts. The quiet determination of students heading toward something they hope will change their lives. The road still carries farm trucks, contractors’ vans, commuters, and weekend travelers. It still does what it has always done: move the region’s lifeblood from one place to another.

Some say the road remembers. If you listen closely, you can hear the old trades whisper-ing through the trees, mingling with the mod-ern engines. Others say the name itself is a kind of blessing, a reminder that work and learning have always lived side by side here.

And maybe that’s the truest folklore of College Highway: a road shaped by hands, strengthened by wheels, and named for the minds that traveled it. A road that has always known where it’s going, even when the people on it do not.

By Lucas Caron

Winter has arrived once again in New Eng-land! Whether you’ve lived here for years or are merely passing through, there’s one thing that defines the season for everyone: frigid storms coating the land with beautiful white snow. Snowfall is indispensable to the way of life of people around the world, and it’s easy to see why; as a child, snow means days off from school, building snowmen, making snow an-gels, sledding with your friends and family, and countless other activities that bring immense joy to the winter season.

The magic of the “winter wonderland” that snow creates is not lost on adults either, for the frosty weather provides ample opportunities to cozy up by a fire with your loved ones, drink hot chocolate as you watch the snow fall, observe the fascinatingly unique designs of each pass-ing snowflake, and much more. There’s shovel-ing too, but I don’t think many people would consider that a fun or “magical” experience. Ei-ther way, much of what we love about winter as a society comes from the magnificent snow that brings chills to our bodies and warmth to our hearts.

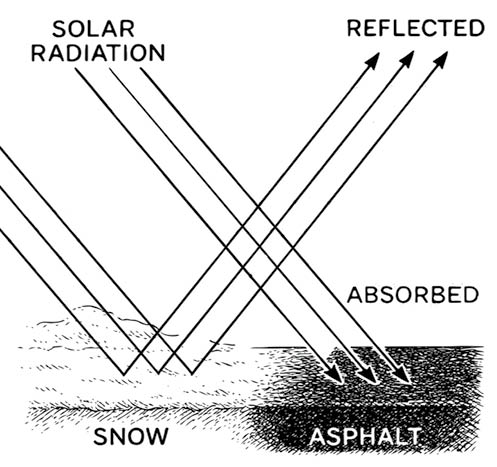

Beyond its cultural relevance, snow also holds key environmental importance for Earth’s plan-etary albedo (pronounced al·bee·dow) through a phenomenon known as the albedo effect. The term “albedo”, derived from the Latin word al-bus, meaning “white”, refers to the measured reflectivity of a surface, specifically in terms of light energy. The amount of solar radiation that a surface reflects into space is represented as a value between 0 and 1, where 0 indicates that no solar radiation is reflected and 1 suggests that all solar radiation is reflected.

Different types of surfaces have wildly dif-ferent albedos; darker-colored surfaces have lower albedos and are more absorbent of solar radiation (such as dark asphalt, which has an albedo between 0.05 and 0.15, meaning it re-flects between 5% and 15% of solar radiation), while lighter-colored surfaces have higher albe-dos and are more reflective of solar radiation. One of the most important high-albedo surfaces on our planet is snow, which has an albedo be-tween 0.8 and 0.9, meaning it reflects between 80% and 90% of solar radiation.

Why is the albedo effect important? Simply put, the amount of solar energy reflected versus the amount absorbed contributes to the level of heat that warms the surface in question. An area with many dark and low-albedo surfaces, such as forests and cities, will naturally absorb much more solar energy and therefore be much warmer than an area with lots of light and high-albedo surfaces, such as a snowy tundra. This is why we frequently observe phenomena such as the urban heat island effect, in which cities con-structed with dark materials like asphalt and concrete are notably hotter than their nearby ru-ral counterparts.

Moreover, the albedo measurements of ev-ery surface on Earth—including land, ocean, ice, and clouds—are averaged to determine our planetary albedo of .31 or roughly 31% of the solar energy that reaches our planet is reflected into space. The albedo of surfaces on a regional level plays a critical role in determining the cli-mate of that region, and our planetary albedo is key to determining the overall temperature of Earth.

With snow being the most reflective of solar radiation, it becomes a key factor in our planet’s regional and global temperatures. Alongside human-induced global warming, the albedo of our planet faces drastic changes. Excess green-house gases in our atmosphere excessively trap and slow heat loss to space via the greenhouse effect, a leading cause of global temperature increases for decades. What amplifies this dan-gerous temperature increase, however, is how it impacts the albedo effect and vice versa through a positive feedback loop known as the ice-albe-do feedback.

A positive feedback loop is when the results of an initial change amplify that initial change. In the case of the ice-albedo feedback, the ini-tial change is the global warming caused by humanity. This warming causes snow and ice around the world to melt, exposing the darker, low-albedo surfaces hidden beneath them. As a result, these new surfaces absorb more solar radiation, leading to increased global warming; and more global warming means more melting of snow and ice. As such, the cycle perpetuates itself, accelerating the speed at which climate change occurs.

Every year, we seemingly get less snowfall here in New England. Yet, unbeknownst to many, it is the loss of that snow to global warm-ing that makes our changing climate a much faster and more devastating threat. This begs the question: what can be done to combat the exponentially growing dangers of the ice-albe-do feedback?

Fortunately, methods of increasing our plan-etary albedo and combating this vicious warm-ing cycle are being researched and developed. This includes “cool roofs,” which are roofing materials that reflect more solar radiation and reduce the amount of heat transferred into a building, as well as lighter-colored pavements and sustainable agricultural practices that con-sider albedo effects. There are even geoengi-neering proposals that center around manipu-lating our planet’s albedo to counteract climate change, such as stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI), which introduces reflective particles into the stratosphere, artificially reflecting a portion of solar radiation into space.

However, geoengineering proposals like SAI are the topic of ethical debates due to their po-tential to disrupt weather patterns and cause unintentional environmental consequences. In addition, artificial albedo increases are not guar-anteed to distribute the resulting cooling effect evenly worldwide, causing regional climate disruptions. Most of all, these strategies don’t necessarily address the foundational problem of climate change: human greenhouse gas emis-sions.

Ultimately, then, the most critical step that must be taken to mitigate the harmful effects of the ice-albedo feedback is the same step that has been echoed by numerous scientists in response to the growing dangers of climate change: re-duction of our production of greenhouse gases on a global scale is paramount. The precious snowfall that defines the winter months here in New England, the life all around Earth threat-ened by dangerously rising temperatures, de-pends on the collective efforts of citizens, world governments, and corporations to reduce harm-ful emissions and work toward a more sustain-able tomorrow. There’s snow place like home, after all—it’s time we work together to protect it, frosty weather and all.

By “Dave Roberts,” VP, Salmon Brook Historical Society

As Granby enters 2026, it is fascinating to look back a full century and imagine what life was like for our residents in 1926—a year shaped by optimism, turbulence, and rapid change. People living in Granby then could not envision the ex-act form of today’s world, yet they felt the same mixture of hope and uncertainty that we do now. Their lives were influenced not only by local concerns but also by global forces and national developments that reached even our quiet New England hills. My cousin Shirley Moore turns 102 in 2026, and from her and other relatives, I have heard fascinating stories about life in the 1920s, 1930s, and beyond.

Globally, 1926 was part of what historians now call the interwar period, a time suspended between the devastation of World War I and the coming storm of World War II. For Granby fami-lies who had sent sons off to fight in Europe less than a decade earlier, the memory of the war re-mained vivid, but the world was moving ahead at astonishing speed. Aviation was capturing the global imagination. Just a year later, Charles Lindbergh would fly across the Atlantic, but by 1926, airplanes were appearing in newspapers and inspiring local students. Cinema and radio were spreading culture across borders. Even in places without local stations, Granby residents knew that radio waves were shrinking distances. International trade and finance were expanding, but with deep vulnerabilities that few recog-nized. The economic optimism of the 1920s felt permanent—though we now know it was only a few years away from collapse. While Granby re-mained an agricultural town, the world beyond its fields was tilting rapidly toward modernity.

Nationally, America was deep into the “Roar-ing Twenties,” a decade defined by prosperity, innovation, and cultural transformation. Manu-facturing was thriving; wages were rising; con-sumer goods like vacuum cleaners, washing ma-chines, and radios were entering ordinary homes. Ford’s Model T was an American icon. Car own-ership tripled in ten years. Even rural communi-ties like Granby were feeling the shift—not just in transportation but in paved roads, gas stations, and travel habits. The sale of alcohol was illegal nationwide, though that rarely stopped the de-termined. Connecticut, like much of New Eng-land, was ambivalent. Speakeasies were not just big-city phenomena; rural stills existed quietly in many towns. And six years after gaining the right to vote, women were increasingly visible in civic organizations, schools, and local govern-ment. To the average Granby resident, America felt both prosperous and modern—but also cul-turally unsettled, with new technologies chal-lenging old ways.

Connecticut in the 1920s was a center of manu-facturing and innovation. Factories in Hartford, New Britain, Bridgeport, and Waterbury pro-duced tools, clocks, typewriters, firearms, and machine parts that reached markets worldwide. Public health improvements were underway. The state was fighting tuberculosis and diphthe-ria, promoting vaccination, and investing in hos-pitals. The Good Roads Movement was trans-forming transportation. Connecticut was paving major routes—setting the stage for today’s state highways. For rural towns, this meant better ac-cess to markets and new mobility for residents.

Rural communities like Granby felt these changes slowly but steadily. Improved roads meant faster trips to Hartford or Springfield, bet-ter delivery of goods, and more opportunities for young people tempted by city life.

Granby in 1926 was still very much a farming community, though the seeds of change were al-ready planted. Tobacco farming was central—broadleaf and shade tobacco supplied ware-houses along the Connecticut River. Dairy farms dotted the landscape, with milk shipped by truck or wagon to regional processors. Cider mills and small orchards played a vital economic role, es-pecially after Prohibition increased demand for non-alcoholic products (and sometimes illicit ones).

Residents in 1926 would recognize some of Granby’s modern values: appreciation of open land, pride in agriculture, and strong community ties. Granby’s population hovered around 1,600 people. Social life revolved around the Grange, which supported farmers and hosted lectures, contests, and community dinners; local churches, which organized social events, volunteer efforts, and youth groups; and schoolhouses, many still one-room buildings, though there was growing pressure to consolidate and modern-ize them.

Evening entertain-ment con-sisted of card games, church sup-pers, barn dances, and the occasional trip to a movie theater in Hartford or Simsbury.

Electricity was reaching more homes, though not yet universal. Telephones were common enough that party lines were a familiar (and sometimes controversial) fact of life. Automobiles were increasing each year, though many Granby families still relied on horses.

These changes created excitement—but also anxiety. Many wondered whether mechaniza-tion and modernization would eventually erase the rhythms of farm life.

What Did Granby Residents of 1926 Expect of 2026? If we could speak to Granby’s residents from a century ago, their vi-sions of the fu-ture would likely have included universal elec-tricity and tele-phones, tractors replacing horses, better roads connecting every home, advances in medicine to fight diseases that still haunted fami-lies, and more educational opportunities for their children

Yet the world of 2026—of smartphones, the internet, electric cars, and a town of more than 11,000 residents—would have been almost un-imaginable. They would marvel at the Granby of today: its thriving schools, preserved open spaces, cultural organizations, and blend of rural heritage with suburban convenience.

Looking back at 1926, we see a community confident yet cautious, rooted in tradition yet conscious that the world was changing. They could not foresee the Great Depression, World War II, suburbanization, or the transformation of Connecticut’s economy—but they lived with re-silience, determination, and faith in progress. In 1945, in less than 20 years, residents gathered to form the Salmon Brook Historical Society, dedi-cated to preserving, celebrating, and sharing the rich history of Granby, Connecticut. Eighty years later, another cadre of devoted volunteers contin-ues to support the Society’s mission.

As we stand in 2026 and look ahead another hundred years, we carry forward the same spirit. Granby’s story is one of continuity and adapta-tion—an enduring partnership between the land and the people who call it home. Happy New Year!

A purposeful lesson lies in every obstacle and setback. Instead of dwelling on adversities, we can choose the high road and keep moving for-ward on rock-solid ground. Nature itself teach-es us this truth.

Consider the black bear. During the harsh winter months, when food is scarce and tem-peratures drop, bears enter a state called tor-por. Their bodies slow down, yet they remain capable of waking, adjusting, and responding when needed. Even in stillness, they are prepar-ing for what comes next. A program coordina-tor for the Arkansas Fish and Game Commis-sion explains that bears intentionally choose the smallest, most constricted dens they can find so they expend less energy staying warm. Their in-stinct is simple: conserve strength, endure the season, and emerge ready for new life. There is wisdom in that—wisdom worth passing on.

Around the world, oth-er cultures intentionally teach their young how to navigate life’s chal-lenges with grace. In Denmark, children as young as six at-tend weekly lessons in empathy. These classes go beyond reading and math; they help children under-stand emotions, practice kindness, and show compassion—especially toward animals. As these children grow, they carry forward the les-sons of respect and emotional awareness, shap-ing a more harmonious society.

When we teach kindness early, we plant seeds that grow for generations. Imagine a world where every child learned to recognize the needs of others, to respond with gentleness, and to value the dignity of every living being. Such small lessons can transform how we in-teract with one another—and with our furry friends too. Scripture reminds us that God is near to the lowly: the lost, the neglected, the excluded, the weak, and the broken. Many of us see ourselves in those descriptions, yet that nearness is precisely where strength begins.

Japan offers another example of preparing the next generation to move forward with pur-pose. The first three years of elementary school focus not on test scores but on learning how to live well with others. Children practice greet-ing people politely, caring for animals, cleaning their classrooms, and respecting nature. Empa-thy, responsibility, and self-control are woven into daily life. Academic subjects are taught, but the emphasis is on steady growth and charac-ter. The results speak clearly: high achievement, near-perfect attendance, and—more impor-tantly—young people grounded in discipline, respect, and community. Real education begins with character, not grades.

Even in our own communities, we see how compassion and resilience can inspire change. A historic restaurant recently experienced this firsthand when two warm-hearted grandmoth-ers visited during the Christmas season. Their kindness, presence, and gentle wisdom moved the owners to reimagine their business with a more inclusive spirit. The Student Prince be-came “The Student Princesses,” a symbolic shift toward honoring the strength and grace of those who lead with love. Their joyful faces, captured in a single picture, remind us that in-fluence often comes quietly—through example, not instruction.

And now we ar-rive at the arrow-head of the story: moving forward with intention. Set your mind on your target. Com-mitment to joy, good health, and purposeful living will always meet resistance—just as an arrow whistles against the wind. Yet it is that very resistance that sharpens our aim.

Hold fast to sound knowledge and a settled heart. These will carry you through trials and service alike. With the right mindset, adversity becomes a teacher rather than an enemy. Fear not, my friends; you are stepping into a produc-tive New Year. Seize opportunities with prepa-ration. Follow through, for the bull’s-eye of suc-cess awaits. You are primed to shine.

Walk through every open door with grati-tude, letting each moment simmer on the fire of a thankful heart. In doing so, you clear a path not only for yourself but for those who follow. This is how we move forward in 2026—by striv-ing, thriving, and teaching the next generation everything we have learned along the way.

By Michael Dubilo

10 Microhabits For

Emotional Regulation

Dr Simone Phillips, Psychologist

Inside the Young Mind:

Granby in 1926:Looking Back and Ahead

We celebrated Christmas not long ago, and it’s hard not to imagine what that first Christmas night must have been like — the night joy broke into the world. Picture a group of shepherds gathered around a crackling fire, sheep scat-tered across the fields like little puffs of cotton, stars glittering above them. Then suddenly the sky splits open and radiant light pours out like a waterfall of molten gold. In the center of that blazing brilliance stand shining beings beyond number.

You fall to your knees, shielding your eyes. A deep, resonant voice vibrates your ribcage: “I bring you good news of great joy!” (Luke 2:10). The sky erupts with music, cheers, and applause. It was all about joy — Joy to the World.

And we still need that joy today. Joy isn’t op-tional. It’s a fundamental psychological and spir-itual need. Without it, life becomes heavy, dull, and overwhelming. With it, life feels hopeful, energized, and full of anticipation. If you’ve lost some of that joy, you can find it again. Scripture says, “I will go to God — the source of all my joy.” God is the source. No matter what weighs you down, you can begin a positive change to-day.

To help you rebuild joy, consider three joy-builders — not joy-busters. They spell JOY: Jettison, Open, Yield. Practice these three, and you’ll feel discouragement loosening its grip and joy rising again.

J – Jettison all regrets about the past

“Jettison” means to throw overboard, to light-en the load. Scripture teaches that if you want to enjoy life, you must let go of the things that weigh you down — and one of the heaviest is regret.

We all have regrets. Nobody’s perfect. We all have moments we’d rather hide. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle once played a prank on several prominent men in England by sending each an anonymous note that read, “All is found out. Flee at once.” Within 24 hours, all eight had left the country. That’s the power of regret and guilt — even the suspicion of being exposed can make us want to run.

But regret doesn’t work. It cannot change the past; it can only make you miserable in the pres-ent. The Bible says, “Forget what happened in the past… I’m doing something new.” To “dwell” means to live somewhere. Don’t live in the past. Learn from it, but don’t live in it.

Everyone has setbacks. Everyone blows it. Ev-eryone fails. In fact, failure is the only way you succeed, because it teaches you what works and what doesn’t. So don’t call it failure — call it edu-cation. Some of us are highly educated!

If I could give you one piece of friendly ad-vice, it would be this: Don’t waste your failures. Learn from them. Try something, and if it doesn’t work, learn and try again. Joy begins when you release the grief, guilt, and grudges of yesterday. Jettison them. Throw them overboard. Lighten the load.

O – Open up to God

This is powerful, and the story of Ben Hooper shows why.

Ben Hooper was born at a time when children without a known father were shamed and os-tracized. By age three, he already knew he was different. Parents whispered, “What’s a boy like that doing here?” In school he kept to himself because no one wanted to befriend him. Satur-days were the worst — walking into town with his mother, he learned that adults could be just as cruel as children.

But when Ben was twelve, everything changed. A new preacher arrived in their small East Ten-nessee town — a man known for kindness. Ben began slipping into church after the service start-ed and leaving before it ended so he wouldn’t have to face anyone. But he loved what he heard, so he kept coming back.

One Sunday he forgot to slip out early. The service ended, and suddenly he was surrounded by people. Then he felt a hand on his shoulder. He turned and looked up into the eyes of the preacher.

“Whose boy are you?” the preacher asked.

The room fell silent. Everyone waited to hear the answer.

Then the preacher’s face softened into a smile. “Oh, I know whose boy you are. The family re-semblance is unmistakable.” The congregation stiffened, unsure what he meant.

“You,” the preacher said, “are a child of God.” Then he gave Ben a gentle swat with his Bible and added, “That’s quite an inheritance you’ve got there, boy. Now go and live up to it.”

Ben Hooper said that moment changed his life. When the picture in his mind changed, his future changed. That shy, rejected boy grew up to be elected — and re-elected — Governor of Tennessee. And he always said his election hap-pened the day he realized he was a child of God.

My friend, you are a child of God. The resem-blance is unmistakable. Before the stars were hung in the heavens, before the mountains rose, before the first human walked the earth — God already knew you, loved you, and envisioned all you could become. Open up to Him. Let Him pour His love into your life.

Y – Yield to God’s influence

Every person wants the same basic things: to be happy, healthy, and reasonably prosperous. But fullness of life comes only when you yield yourself to God.

Think of the story of Lawrence of Arabia trav-eling to Paris with a group of Bedouins. These desert nomads were astonished by the abun-dance of water — rivers, fountains, hot and cold running water in their hotel rooms. When it was time to return home, Lawrence couldn’t find them. He finally discovered them in their rooms, tearing the faucets off the sinks and stuffing them into their suitcases.

They believed that if they brought the faucets back to the desert, they’d have all the water they wanted. They didn’t understand that a faucet without a water source is useless. It runs dry.

Human beings are the same. We must be con-nected to the Source. If we want the good things in life — peace, purpose, joy — we must stay connected to the One who gives them.

Some of you feel a little empty inside. You have a nice home, a nice car, a nice family, a nice job — but still there’s a thirst that never quite goes away. Jesus said, “He who believes in Me will never be thirsty.” Yield to His influence. Let Him fill the deepest places of your soul. Want a joy-filled life?

Jettison your regrets…

Open up to God, and…

Yield to His influence.

Joy to the

World

To include your event, please send information by the 1st of the month. We will print as many listings as space allows. Our usual publication date is around the 10th of the month. Email to: magazine@southwoods.info.

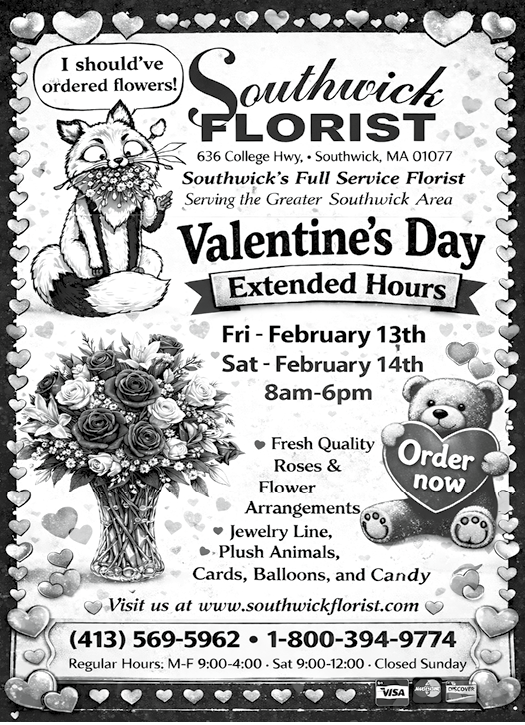

Southwick Historical Society Inc

America 250 Events

Sunday Jan 25—General Knox & the Knox Trail—Bob Brown—Meeting House Hall, 222 College Highway Southwick—2 P.M. (*Snow Date: Sunday Feb 1)

Thursday March 26—Lt. Richard Falley Jr.: Revolutionary Soldier and Armorer—Meeting House Hall, 222 College Highway, Southwick—7:00 P.M.

Tuesday July 28—“Our People, Our Patriots: Stories of real everyday citizens from our and neighboring towns who played a role in the American Revolution”—Dennis Picard—Southwick Public Library, Rebecca Lobo Way, Southwick—6:00 P.M.

August 2—250th Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence— Southwick Congregational Church, 488 College Highway, Southwick—Time to be announced

November 11—Veterans of the Revolutionary War—Old Southwick Cemetery, 322 College Highway, Southwick—Time to be announced

10-5

Stanley Park

History Program

February 19 Westfield, MA − Stanley Park of Westfield in collaboration with the Westfield Athenaeum invites the community to step back in time during a special Stanley Park History Program on Thursday, February 19, from 3:00 to 5:00 p.m. The program will be held at the Westfield Women’s Club, 28 Court Street, Westfield, MA.

Local historian Robert Brown will lead an engaging discussion on the origins of Stanley Park, tracing its beginnings in 1949 and highlighting the people, vision, and preservation efforts that shaped the park into the cherished community space it is today. Brown’s dedication to uncovering and sharing Westfield’s history earned him a Westfield Preservation Award from the Westfield Historical Commission in 2023.

Attendees will also enjoy a screening of the 8-minute documentary, Stanley Park: Rooted in the Past, Growing for the Future, which captures the park’s history, mission, and enduring impact. Stanley Park staff will be on site to answer questions about the park, upcoming programs, and ways to get involved during the upcoming season.

Light refreshments will be served. This free program is open to the public and offers a meaningful opportunity for longtime supporters and new visitors alike to deepen their connection to Stanley Park.

For questions or additional information, please contact the Development Office at 413-568-9312 ext. 108 or email development@stanleypark.org.

Southwick Public LibraryUpcoming Events

January 28, 3:00pm - 4:30pm Adult Craft: Pinecone Snowmen — Join us to create a cheery pinecone snowman perfect for the chilly weather. Registration is required and opens January 9 at 10am.

January 29, 2:15pm - 3:15pm Teen Snowman Craft — Join us in the community room to paint and decorate a wooden snowman! Registration Required.

February 2, 3:00pm - 4:00pm Adult Craft: Button Mittens — Use a variety of buttons to create a cute mitten display on a canvas. Registration is required and opens January 16 at 10am.

February 4, 6:00pm - 7:00pm Stop the Bleed Training — Registration required. A bleeding injury can happen anywhere. Instead of being a witness, you can become an immediate responder because you know how to STOP THE BLEED®. You’ll gain the ability to recognize life-threatening bleeding and act quickly and effectively to control bleeding once you learn three quick techniques. Our instructors will teach you live—in person, using training materials specially developed to teach bleeding control techniques. They will be available to check your movements as you practice three different bleeding control actions. They will keep working with you until you demonstrate the correct skills to STOP THE BLEED® and save a life.

Valley Student Theatre

Valley Student Theatre’s

Big Item BINGO Night

FEBRUARY 28TH 6-10pm − Join us at American Legion, Post 80 Enfield, CT for a Bingo night to support the Valley Student Theatre! Looking for an exciting way to spend your evening? Join us for Bingo Night and experience the thrill of winning big while having a blast with friends and family! Raffles, silent auctions, and other amazing prizes! TICKETS AVAILABLE ONLINE OR AT THE DOOR! For more Information and to sign up please go to www.valleystudenttheatre.org

Autism Workshop

Sunday, February 15, 2026 6:00 PM ET This FREE workshop is designed for parents who want to better understand autism through a nervous-system and Reflective Parenting lens, without overwhelm or pressure to fix anything. Scan to register.

COUNTRY PEDDLER

CLASSIFIEDS

GOODS & SERVICES

DELREO HOME IMPROVEMENT for all your exterior home improvement needs, ROOFING, SIDING, WINDOWS, DOORS, DECKS & GUTTERS extensive references, fully licensed & insured in MA & CT. Call Gary Delcamp 413-569-3733

RECORDS WANTED BY COLLECTOR - Rock & Roll, Country, Jazz of the 50’s and 60’s All speeds. Sorry - no classical, showtunes, polkas or pop. Fair prices paid. No quantity too small or too large. Gerry 860-402-6834 or G.Crane@cox.net

GOODS & SERVICES

Lakeside Property management - For all your landscaping needs. Mowing, new lawn installs, sod, mulch/stone installation, bush trimming, retaining walls, snow plowing/removal, etc. Serving Southwick, Suffield, Granby, Agawam, Westfield, Simsbury. Residential and commercial. Call Joe 413-885-8376. Give us a call and let us get that property looking the way you want it! Now accepting major credit cards.

The granby motel- 551 Salmon Brook Street Granby, CT 06035. Room for rent, weekly, daily, & monthly. Wifi available. Stove, Refrigerator, Kitchen. LONG TERM RENTAL AVAILABLE AT AFFORDABLE PRICE. Ask for Mike Shaw. 860-653-2553

St. Jude’s Novena - May the sacred heart of Jesus be adored, glorified, loved and preserved throughout the world now, and forever. Sacred Heart of Jesus pray for us. St. Jude, Worker of Miracles, pray for us. St. Jude, Helper of the Hopeless, pray for us. Say this prayer 9 times a day. By the 8th day your prayer will be answered. It has never been known to fail. Publication must be promised. Thank you St. Jude. ..- MM

St. Jude’s Novena - May the sacred heart of Jesus be adored, glorified, loved and preserved throughout the world now, and forever. Sacred Heart of Jesus pray for us. St. Jude, Worker of Miracles, pray for us. St. Jude, Helper of the Hopeless, pray for us. Say this prayer 9 times a day. By the 8th day your prayer will be answered. It has never been known to fail. Publication must be promised. Thank you St. Jude. ..- DG