As the air gets crisper and winds more blustery, millions of New Englanders turn their thoughts to one issue: how to keep warm without turning the thermostat up.

Besides the long johns, sweaters, and TV sacks, here are a few more tips to warm the cockles of your heart, and hopefully, the rest of your body as well . . .

If you own an electric blanket, but don’t feel comfortable sleeping with it on or have the misfortune to be married to a cheap-skate who won’t let you keep it on, don’t be dismayed. You can do one of two things. Turn the heat on half an hour before you re-tire, then switch it off. This will at least spare you from cold-sheet-shock syndrome. And once the bed is warmed up your body heat will take over to keep it warm. Or, don’t turn it on at all. Spread the blanket as smoothly as possible underneath your bottom sheet. Your body will heat up the wires in the blan-ket, and reflect the heat back up to you. You have to actually try this idea to see how well it works. And it works, fast, too!

Nov 1984

Tuesday night was windy. High tide water is only several feet below the “Anchor’s” parking area. Great waves against the sea wall sent fountains of salt spray to soak parked cars. About ten I went out and moved the Plymouth up the hill.

The Anchor and Ark has a piano. I tried to play during supper when no one was around, but the F-sharp key stuck and the landlord liked to talk so I didn’t get much done.

Allen Jensen, from Quincy, a Senior Engineering Aid (like me) engaged our third floor rooms for us. He is inspector for a Chapter 90 resurfacing job on Bradford Street. He is in room number six, Louis has eight, and Ernie and I share number nine. Jensen is very social. He came to our room at 9:30 to read magazines. Ernie went out and didn’t come back. It became a game of how to avoid “Kid Dooflicker” as Ernie calls Jensen.

Anchor and Ark Club in 1949, Prov-incetown, MA. Photo by A.E. Rapisarda

By Clifton J. (Jerry) Noble Sr.

My widowed mother, Minnie E. Noble, nicknamed “Hester” by me, was 62 this month. I was 23. May 1st we started Montgomery living in our remodeled country schoolhouse without electricity or running water. I had worked two years in a survey party for Massachusetts Department of Public Works and was now transitman. I’d just replaced my 1948 Crosley car with a new 1949 Plymouth. Work in Greenfield District 2 had slowed, and we were transferred to the Cape. My journal gives November doings.

November 12, 1949, Saturday. The week of October 31 to November 4 I drove my new Plymouth to Provincetown so Hester could go with me and spend the week. Party chief, Louis Johnson, Ernie Rapisarda and I stay at the Anchor and Ark Club. I got a room for Hester with the Cordeiros at the Standish. She took many walks and ate with extreme economy. Wednesday evening I took her and Ernie for a ride out to Race Point lighthouse.

Nov 2009

Friday there was a cloudburst. Louis, with the state carryall and Ernie, and Hester and I in the Plymouth, started home. At new construction we found mud a foot deep with a school bus stuck in it. We made a seven mile detour through South Truro to rejoin the state highway at Wellfleet. I followed Louis to Taunton where he took Route 140 to stay in Massachusetts.

Hester and I went on through Rhode Island but were stopped by a state trooper in Dighton. He was very nice. No charges. Later I discovered that a wrong gear makes my speedometer read 20% slow.

Home again on Saturday I piled firewood, and fitted plywood panels to block cracks in the front door. I also blocked holes in the shed wall which let cold drafts into the kitchen.

Hester had planned to stay alone at the schoolhouse but changed her mind and caught the 2:30 bus to Westfield to stay with Minnie Finney.

I went to P’town in the truck with Louis and Ernie. The first night we escaped “Dooflicker” by going to bed early. Next night he missed us at supper and knocked on our door. Ernie was writing postcards and I was in bed. We turned out the light. We heard him ask Louis where we were. Loius said, “They’re in there.” Jensen opened our door and barged right in. Ernie crouched over the bedside table writing cards. His bags and clothes filled the easy chair and mine draped the straight chair. Ernie’s bed was littered with paper and stamps. Mr. Jensen the impeccable sounded miffed and didn’t stay long.

At work on a Truro hill I heard a bullet whine. Then Louis heard one and said, “Let’s get out of here.” We heard no shot sounds to reveal whence the bullets came.

Wednesday night Loius got a phone call from Supervisor Bob Broomhead that Tattan wanted us back in District 2. We were hilarious. I even played a game of pool with Ernie and lost every ball. After clearing up loose ends in our work we turned over the survey books to Slade’s party and left for home.

What a great name! It’s short, easy to say. It’s distinctive, being the only Southwick in the United States. It seems ap-propriate, being on the southern border of Massachusetts, and indeed a few miles fur-ther south than all of the other towns from Webster to Sheffield on the 100-mile bound-ary with Connecticut. It’s not usually prone to confusion, other than the small hamlet of Southfield, Mass. farther west, and of course Southwick’s Zoo in Mendon.

So how did our town come to have this name? It’s a mystery. When the residents petitioned the Massachusetts provincial government to be separated from Westfield, they referred to themselves as being from the “Southardly part of Westfield.” When the approved charter finally came back from Boston, the name was Southwick. Who in Boston chose this name and their rationale is lost to history.

Southwick:

The Mystery of Our Name

Southwick:

The Mystery of Our Name

by James Putnam II

Photo of Broad Street looking south. Gladys Reed’s horse is drinking from the watering trough at the intersection of what is now College Highway and Depot Street

As a child I was told that Southwick was a manufactured word referring to the South Bailiwick of Westfield. Drop the “Baili” from the middle and you have Southwick. Baili-wick is an old English term for town or vicin-ity. Again, there is no evidence that anyone in Westfield or what later became Southwick was referring to this area as a bailiwick. There is some logic, however, to an obscure colonial official in distant Boston coining the name based on what he was reading about “Southardly part” in the petition.

Any good mystery has more than one plau-sible explanation. The second “suspect” is that the name honored someone with the last name Southwick. From the earliest days of settlement, Southwicks had emigrated from England to the Massachusetts Bay Colony:

• John Southwick arrived in Salem some-time between 1620 and 1650

• Lawrence Southwick, a Quaker, arrived in Salem in 1630

• Provided Southwick settled in Salem in 1639 (Yes, Provided was a first name back then!)

Lawrence Southwick’s descendants were quite successful in the North Shore area. To-day, there is a historic Southwick House built by that family around 1750 in Peabody, Mass.

Certainly Mass. towns were sometimes named after famous people – Amherst, Lee, Belchertown, Warren, Washington, and Han-cock are all from this genre. However, there is no prominent person named Southwick from that era who would seemingly have risen to the honor of having a new town in western Mass. named after them. So, this is probably the least likely explanation, unless there were some sort of 18th century “inside job” by someone named Southwick!

That brings us to what I view as the most plausible explanation. Southwick and several of its name variations are a fairly common place name in England, akin to how com-mon Springfield is across the USA today. Last year, my friend and likely distant rela-tive Robert Putnam in England told me that there are dozens of places named Southwick. It’s an old name going back to Anglo-Saxon times, i.e., 410 to 1066 AD. If a more elegant yet traditional English name was needed for a newly incorporated town calling itself the “Southardly part,” why not a common, tradi-tional place name from Old England? Recall that in 1770, the Province of Massachusetts Bay was still very much part of the British Empire despite developing political tensions such as the Boston Massacre early that year.

There are Mass. place names with a direct connection to a place in England, e.g., Plym-outh and Springfield. There is absolutely no evidence of any such connection for South-wick. It was being settled by families who had already lived in New England for several generations, moving in from older towns. Be-sides, the name seems to have been assigned in Boston and not locally.

Southwick 250 recently formed a friend-ship with the Town of Southwick in the Adur Administrative District on England’s south coast. Knowing that there was no direct con-nection other than the name of which we are equally proud, we agreed to call ourselves Southwick Neighbors across the Pond. It will be fun sharing and learning about the natural beauty, heritage, community and pride of each other’s Southwick on both sides of the Atlantic.

Now let’s speculate on possible alternative names!

Oct 1982

In February 1823 the Hampshire and Hampden Canal Company was incorporated and secured a charter authorizing it to construct and operate a canal from the Connecticut River through the towns of Northampton, Easthampton, Southampton, Westfield and Southwick, to the Connecticut line; there to connect with the contemplated Farmington canal running from New Haven northward to the state line.

Money for the construction of the canal was to be raised by bond subscriptions. Both canal companies experienced difficulty in collecting the pledges. Subscriptions came in slowly that construction could not start. Finally in 1826, it was decided to merge the stock of both companies.

Actual work on the canal commenced on November 1, 1826, in Southwick Village near the state line and was soon followed at points between there and Westfield. To construct such a canal today would be a comparatively minor roble, but 150 years ago it was an engineering feat of gigantic proportions. Power was in the backbone and muscle of men, horses and oxen. The work was let out to local subcontractors and the can was built in sections.

The Congamond Lakes, then called the Southwick ponds, were utilized as far as available, a channel having been cut to join the north and middle ponds. From the ponds, the canal extended through the Powder Mill Brook section into Shaker Village, to Little River and northwest to the Basin at Westfield Harbor. The railroad tracks of the New Haven & Northampton Railroad later followed the canal route through Westfield.

At last in 1829 the canal was pushed across the state line. On the first Monday in October the canal boat “Sachem” of Granby came up to the locks opposite Southwick Village and within five miles of the Basin in Westfield Harbor. It carried 150 passengers accompanied by a band of music.

A month later the “General Sheldon”, built and owned by M.Z. Bosworth of Westfield, was launched at the Westfield Basin. On December 9th this canal boat left on her first voyage to New Haven. On the return trip her cargo consisted of coal, salt, molasses, oranges, codfish and flour.

If you’re getting enough vitamins and min-erals, but still get feet and leg cramps at night, try keeping your feet and legs extra warm. Wool socks and leg warmers may look a little strange, but it sure beats waking up out of a sound sleep to jump out of bed and pace the bedroom floor in agony.

A nightcap is not necessarily something you drink (although a little shot of brandy will warm yur innards nicely). A nightcap is also something you wear to bed. It will give you a quaint, nostalgic look and at the same time keep your body heat from escaping through the top of your head. (Did you know that at least 40% of your body heat escapes this way?)

If you are going to use the oven at any time during the day, schedule it for early morning. This will help take the morning chill out of the house, and make it less of a strain on your heating system to keep the house warm afterwards. Also, you could have sup-per made early in the day and have time for a nap in the afternoon!!

Our three-burner cooking plate in the kitchen has been using gas from our first tank for seven months. We have ordered three cords of wood from Percy Helms as the living room stove takes it fast this cool weather. Hester pulled up some seedling hemlocks and I set them out along the stone wall and in back of the well.

Louis gave me a broken 100-foot steel tape and loaned me the mending kit. If I can make a reel for it, I can make a tape survey of my property.

November 25, 1949, Friday. The pump on the well froze Monday night and it took several editions of newspaper to thaw it out. Tuesday and Wednesday the temperature went to 14 degrees in some places.

We attend Sunday evening service at the Advent Christian Church which pleases Uncle Ralph. Before church we went to a birthday party for Minnie Finney.

Yesterday we went to Uncle Ralph’s on Mort Vining Road in Southwick for Thanksgiving dinner. All five sons (except Ralph Junior) and spouses were there, also daughter Mabel and husband, Howard Johnson.

Today I completed the door with mirror for Hester’s bedroom closet. Hester likes the house very warm. Working in briefs I was surprised by visitors. I dropped the door and smashed the mirror. Luckily I had another one the same size to put in.

The callers were Myron and Etta Kelso. Just as they left Mary Rivard walked up the road. She went by to see the new bridge over Bear Den Brook and stopped in on her way back.

Now that you’ve put on a few pounds from all the goodies you’ve been baking early in the morning, why not start an exercise pro-gram? Invite the neighbors over to join you. Nothing warms the room up faster than a bunch of sweaty people doing jumping jacks! And come spring when you peel the long johns off, you’ll be glad to see your body’s in half-decent shape!

Curl up in a recliner or armchair with your kids, a blanket, and a stack of books (teen-agers may resist!) The housework can wait. It’s hard to work with numb fingers, anyway.

If all else fails, keep your husband home. Even if he can’t bake, he can generate body heat!

November 27, 1949, Sunday. Snow all day. Charles Peckham was over in the pine woods beyond the meadow cutting trees for lumber. I went to help. On leaving, Charlie found he had left his bag of saw-adjusting tools in the woods. For twenty minutes we searched where he thought he had left them. Finally I affirmed, “With God there is nothing lost.” About 25 feet in a new direction I found the bag almost covered with snow.

Percy Helms delivered our last order of firewood, and I helped him unload. Coming up the mountain he almost slid off the road. After dinner I piled wood beside the house, brushing off each piece and covering it. Three cords isn’t very big.

After dark I walked two miles to Russell for the newspaper. It took about 25 minutes going down. Coming back, Joe Rusin picked me up at the river bridge and brought me as far as his place, so I was home 20 minutes before Hester expected me. Three cars without chains have passed since snow got deep. This gives me courage for tomorrow. Deer season opens December 5 through 10. I believe the daily hours are 6:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. I hope there won’t be many hunters around here.

• Southardly seems awkward.

• South Westfield seems prone to confu-sion, and certainly fails to be unique.

• Poverty Plains, the original name for the first settlement around The Ranch and the old Southwick Golf Course, would surely have had negative connotations.

• Congamuck, the original Nipmuck name for our lakes, might not have stood the test of time. Anyway, in 1770, the fate of our jog and its two southern ponds was still in question.

While we’ll likely never know for sure, all of this is just my view. Here’s an added bonus. “Southwick means a south dairy farm” in the original Saxon language from over 1,000 years ago (http://www.localhistories.org/southwick.html Tim Lambert). Given all of the family dairy farms that once dotted the gentle hills of our Southwick, especially to the west of Route 10, this seems like an especially fitting coincidence to the name Southwick.

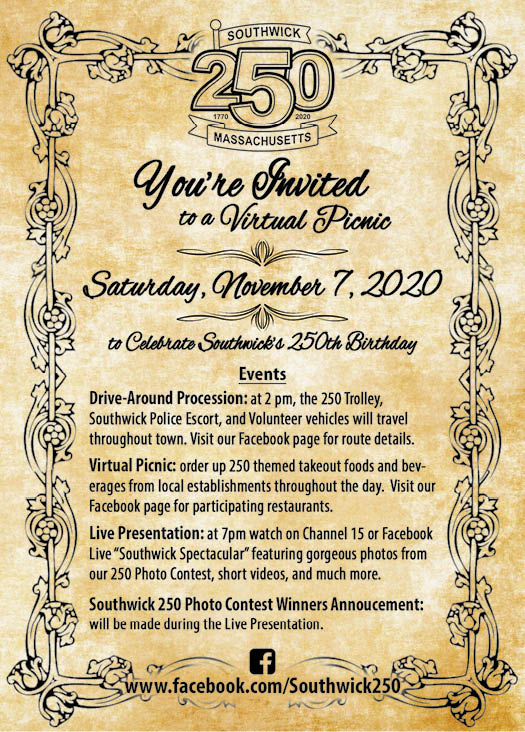

So, we became Southwick on November 7, 1770. It’s a wonderful name for a great community of hard-working Americans of diverse origins and beliefs. Be proud!

Washrooms (small tiny cubicles with toilets) were provided with an ample supply of water. The meals were excellent, with each boat captain striving to outdo his competitors. In May 1841 it was recorded that from Westfield to New Haven was $2.25 or $3.75 if bed and meals were included. Advertisements told of boats “handsomely fitted up”.

The second type of canal boat was pure barge with old scow lines. They, too, were gaudily painted. These were the freight boats and were equipped with cookstove lockers and usually four bunks for the crew. Barges carried the products of the north to New Haven; chiefly wood, shingles, cider, hides, potatoes, pork, wool in bales, tar, turpentine, cheese, charcoal, lumber and agricultural products. Coming back from New Haven, the cargoes were of coal (which was hitherto unobtainable above tidewater and very costly), rum. Carved rosewood parlor sets upholstered in horsehair, and occasional pianoforte, salt, oil, oysters and iron work such as stoves.

The trip along the canal through the country must have been very comfortable for people who had never dreamed of a parlor car and who were in no nervous haste to reach their destination. They had never conceived of any faster mode of travel than by relays of horses, over roads which made speed bone-racking.

One aspect of the canal is the romance and fun it provided. In winter, skating parties were organized and races held, in summer, swimming parties and innumerable picnics frolicked along its banks where the children and grown ups, too, could watch the colorful proceedings as the boats passed by. On holidays there were special excursions and many visits and pleasurable trips were made from town to town. Many a happy couples idled downstream in a homemade row boat. Parents traveled to commencement exercises at Yale College by canal boat and mothers sent laundry and packages to their offsprings at Williston Academy. The canal indeed brought much interest and excitement into the lives of those it touched.

Until the winter of 1847-48, the canal was an active operation. Although extraordinary maintenance expenses ate up what otherwise would have gone into dividends. In 1845, although business was excellent, the Directors realized that the railroad was the coming means of transportation and secured an amendment to their charter permitting construction and operation of a railroad intended to handle passenger and express business, the canal to carry the heavy freight.

Quite often two horses ridden by small boys and driven tandem were used on the towing path, but for hard pulls of heavy cargo, two spans of horses up to five were used. Sometimes oxen pulled the cargo boats. Long tin horns called for the opening of the locks and summoned the passengers as well.

The ladies cabin forward was usually painted in bright colors, while more somber shades were used for the gentlemens cabin. Hulls were crimson with a wide white band at the water line. The superstructure, which consisted of the combined cabins set on deck, was another color. Each cabin was low and narrow, with its small windows brightly curtained in calico. Some of the canal boats dispensed hard liquors at a bar in the men’s cabin.

Both cabins were fitted with berths, which were tipped up against the walls in daytime, out of the way of tables and chairs set up for serving meals. Meals, like sleeping accommodations, would be included in the cost of the ticket. Let down at night, the berths were furnished with blankets and linens and surrounded by curtains for privacy.

With the opening of the first section of the Canal Railroad through Plainville, Connecticut, it was at once seen that the public wanted only the railroad service and the canal was not again officially operated, although for some time parts of it were used at their own risk by owners of canal boats.

The canal had served well. A gigantic enterprise in a colorful era, it made a great contribution the growth and expansion of both Connecticut and Massachusetts.

Excerpted for Westfield, Massachusetts, 1669-1969, Edited by Edward C. Janes & Roscoe S. Scott, Copyright 1968, Westfield Tri-Centennial Assn., Inc.

Canal from left bank of

Congamond Lake opposite Babb’s

Beach. From Southwick Bicentennial Book

“There’s more to a blue jay than any other creature,” wrote Mark Twain. Indeed, few wild animals can rival the blue jay in the beauty of its plumage, its repertoire of sound or in its ability to adapt to man. For these reasons, the blue jay has become one of America’s best known and most popular birds.

Nearly everyone has come in contact with this species at one time or another. Jays are distributed throughout eastern North America and are commonly found year round. The bird’s elegant crest, dapper blue coat and black necklace readily distinguish it from all other birds.

November 1984

Article and Artwork By Walter Fertig

The feature for which the blue jay is best known is its vocal ability. Blue jays are noisy and call frequently, whether they are alone or in a flock. Much of their shrieking is directed at enemies and serves to warn other animals of danger. But often it seems the jay is crowing solely for its own pleasure.

Blue jays are accomplished mimics of other birds. They emit a whispery song similar to the vocalizations of wrens, chickadees and other small songbirds. Jays can also imitate the harsh screams of their dread enemies, the hawks.

The only time the blue jay becomes quiet is during the spring nesting season. In courting a mate, the male jay collects twigs and brings food. If his offerings are found to be acceptable, the pair will proceed to search for a nesting site in a thicket of evergreens. Once a suitable branch is found, the birds construct a nest from twigs, bark, grass, and if near civilization, roadside litter.

Both birds actively defend their nest. The 4-6 speckled eggs hatch within two and a half weeks of being laid. Over the next three weeks the male is kept busy providing for himself, his mate, and the giant appetites of his brood.

November 1984

Drain pineapple liquid into a measur-ing cup. Add enough milk to make one cup. Combine with egg and orange rind. In a separate bowl, sift together flour, sugar, bak-ing powder, salt, and nutmeg. Blend milk mixture into dry ingredients, along with the melted butter, mixing just until batter is blended. Stir in crushed pineapple. Spoon into lightly buttered muffin pans. Bake at 400 degrees for 20 minutes or until golden and set. Cool slightly then remove from the pan and serve warm.

Pineapple Muffins

1 Can (8 ½ oz.) crushed pineapple

1 ½ tsp. Grated orange rind

¼ cup sugar

¼ tsp. Salt

¾ cup milk

¼ tsp. Nutmeg

¼ cup melted butter or margarine

1 egg slightly beaten

2 cups sifted all purpose flour

1 tablespoon baking powder

Sift flour, baking powder, cinnamon and salt into large bowl. Beat eggs and sugar to-gether in a medium size bowl with an elec-tric mixer until fluffy. Stir in oil and carrots, mix well. Pour into dry ingredients moist-ened (do not over mix), stir in nuts. Pour in a greased and floured 10 inch tube pan..Bake in a slow oven (325 degrees) for 1 hour, or until the top springs back when lightly pressed with fingertip. Cool in a pan on a wire rack for 10 minutes. Loosen around the edges with spatula, turn out of the pan and cool completely. Frost as you wish.

Quick Carrot Cake

3 cups sifted all purpose flour

3 tsp. baking powder

2 tsp. baking soda

2 ½ tsp. Cinnamon

½ tsp. Salt

4 eggs

2 cups sugar

1 cup Crisco oil

2 junior size jars baby food carrots (7 1/2oz. each)

1 cup chopped walnuts

In a mixing bowl, cream shortening and sugar. Add eggs, one at a time, beating well after each addition. Combine flour, bak-ing powder, nutmeg and salt; add to the creamed mixture alternately with milk. Fill greased muffin cups two thirds full. Bake at 350 degrees for 18 minutes or until a tooth-pick comes out clean. Cool for 5 minutes be-fore removing from the pan to a wire rack. Dip doughnuts in melted butter or mar-garine then roll in cinnamon-sugar. Serve warm

Lazy Donuts

2 tbsp. plus 1 ½ teaspoons shortening

½ cup sugar

2 eggs

6 tbsp. Milk

2 cups all purpose flour

2 tsp. Baking powder

½ tsp ground nutmeg

½ tsp. Salt

Butter or margarine

All of us live in a tent. In fact, we live every day, and sleep every night, in one of two tents: Content or Discontent. How about you? Where have you been living lately?

You say, “Well, Jeff, under the circumstances …” What do you mean “under the circumstances?” What are you doing under the circumstances? You’re not going to be comfortable living under the circumstances … any more than you’re going to be comfortable sleeping under your mattress!

Today I want to talk to you about rising above your circumstances – rising above, with God’s help. This month as we celebrate Thanksgiving, let me give you three thoughts – three simple thoughts – that will move you from one tent to the other.

Ready? The first thing you have to do to create an attitude of thanksgiving and a feeling of contentment is …

Think Thanks

Three Keys to Contentment

1. Appreciate the good things that God has given you.

Everything may not be perfect in your life. But if you don’t learn to be happy where you are, you will never get where you want to be. You may not have the perfect job but thank God you’re at least employed. You know what? There are plenty of people who would love to have your job.

The Bible gives us some good advice: “Be joyful always; pray continually; give thanks in all circumstances.” (1 Thessalonians 5:16-18) That means instead of dragging around every day feeling sorry for yourself, you’ve got to change your focus. Our attitude should be: “I’m going to quit looking at what’s wrong in my life and start being grateful for what’s right.”

I want to be like the 92-year-old man I heard about. He was being moved into a Nursing Home for the first time. His wife of 70 years passed away, making the move necessary. As he maneuvered his walker to the elevator, the nurse began to describe his room. “I love it!” he said.

“Mr. Jones, you haven’t even seen it yet.”

“That doesn’t have anything to do with it,” he replied. “Happiness is something you decide on ahead of time. Whether I like my room or not doesn’t depend on how the furniture is arranged … it’s how my thoughts are arranged. I have already decided to love it.”

He added: “It’s a decision I make every morning when I wake up. I can spend the day in bed moaning about all the parts of this 92-year-old body that no longer work so good, or I can get out of bed and be thankful for the parts that do work.”

Folks, let’s be like that 92-year-old. Let’s quit looking at what’s wrong with our life and start being grateful for what’s right. What am I saying to you? Instead of complaining …

2. Think Thanks: Acknowledge every blessing.

Once there was man who had a dream … a dream that he went to heaven. An angel was showing him around. First, the angel showed him a great big, busy room, filled with angels. The angel said, “This is the Receiving Department. Here, all the prayers from all over the world are coming in constantly, being received, and being sorted out.”

They moved down a long corridor and came to another room. “This is the Packaging and Delivery Department. Here all the answers to prayer are being processed and delivered to earth.” The room was very, very busy, with many, many angels coming and going.

Finally, they got to the farthest end of the corridor. They stopped at the door and looked into a very small room. To the man’s surprise, only one angel sat there, idly doing nothing.

“What happens here?” the man asked.

“This … well, this is the Acknowledgement Department,” his angel friend told him. He seemed kind of embarrassed.

“How come there’s not more work going on here?” the man asked.

The angel sighed. “Well, the fact is, after people receive the blessings they asked for, very few send back acknowledgements.”

The man asked, “How do you acknowledge God’s blessings?”

“Simple,” said the angel. “Just say, ‘Thank You, Lord.’”

“That’s it? Just say, ‘Thank You, Lord.’ One more question: What blessings should we acknowledge?”

“Well, if you have food on your table, clothes on your back, a roof over your head, and a bed to sleep in … you are richer than 75% of people alive in the world today.

“If you have any money in the bank, in your wallet, or spare change in a jar … you are among the top 8% of the world’s wealthiest people.

“If you own a computer … you are part of the 1% of the world who has that opportunity.

“If you have never experienced the terror of battle, the loneliness of prison, the agony of torture, or the pangs of starvation … you are more blessed than 700 million people in the world today.

“If you have any money in the bank, in your wallet, or spare change in a jar … you are among the top 8% of the world’s wealthiest people.

Fortunately for the male bird, jays are not fussy eaters. Their diet is made up mostly of vegetative matter, supplemented by insects, spiders, mice, frogs and salamanders. During the spring, blue jays are a major predator of crop-eating caterpillars, and provide a beneficial service for farmers and home gardeners alike.

Jays also aid man by helping perpetuate their forest habitat. In the fall, blue jays feed heavily on acorns and nuts, and will often bury them underground for future use. Some of these acorns are forgotten and will eventually grow into new white oaks. When chestnuts were more abundant, jays inadvertently helped plant them as well.

In spite of their many benefits to man, blue jays have acquired a bad reputation among some bird lovers. Jays are criticized for their belligerent behavior at the backyard bird feeder and for occasionally feeding on the eggs and nestlings of other songbirds. John James Audubon’s portrait of the blue jay depicting a flock attacking a nest has done much to brand the bird with a rogue image. In truth, jays are not major threats to other birds and their reputation is largely overblown.

Blue jays themselves have many enemies, especially hawks, owls and other birds of prey. Jays are most vulnerable to attack in open fields and pastures and therefore are more commonly found in forested areas.

The bird that blue jays seem to fear and hate the most is the owl. If a flock of jays encounters and owl in the woods during the day, they will mob it relentlessly until it retires deeper into the forest. When night time comes, however, jays treat owls with more discretion.

Before the advent of home bird feeding, blue jays were migratory. Each fall they would gather in large flocks and spend the winter in the southern states. While some jays still migrate, more and more stay behind to feed on man’s offerings.

The blue jay’s ability to adapt to man’s presence has aided the species’ survival. Even with the destruction of much of its original habitat, blue jays have been able to hold on and expand their range. Few other birds have been as successful at coping with man.

“If you woke up this morning with more health than illness … you are more blessed than many who will not survive this day.

The man interrupted the angel. “Okay, I get it. I need to say, ‘Thank You, Lord,’ like a million times a day!”

Folks, that’s what I’m telling you! Think Thanks. Cut your complaining. Acknowledge your blessings. Make up your mind to be happy.

Don’t just take it from me. Take it from the Bible. The Bible says, “Give thanks to the Lord for He is good, and His love endures forever … Forget not all His benefits.” (Psalm 136:1, Psalm 103:2)

And even if things get really tough, even if things aren’t going your way, remember this …

3. God loves you and will never leave you.

A grandma and her little freckly-faced grandson were spending the day at the zoo. Lots of kids were waiting in line to get their faces painted.

An older girl in front of the line took one look at the little boy and said, “You’ve got so many freckles on your face, there’s no place to paint!”

Embarrassed, the little fella dropped his head and stared at the ground.

His grandmother knelt down next to him. She took her hand and gently lifted his chin, until he was looking in her eyes. She said, “I love your freckles. I always wanted freckles!” She traced he finger over his little, smooth cheek. “Freckles are beautiful – as beautiful as a starry sky!”

“Really?” said the little boy.

“Of course! Why, just name one thing that’s prettier than freckles.”

The little boy reached up and touched his grandmother’s face. Then he softly whispered, “Wrinkles.”

There were two types of boats used on the canal. In reality they were huge ponderous barges with low superstructures, towed by means of a long rope or ropes, by horses or mules walking along the towpath.

One type was called a packet. On these, excursions were held with honeymooners and sightseers, many of the packers servicing excellent meals and all heightened by band music. Usually some cargo was also on board.

The boats passed into the locks from a pond basin, these being the only points where the boats passed each other. There was a bumping post as the entrance of each lock. While the tedious wait for raising and lowering the water in the locks was progressing, taverns and inns situated nearby did a thriving business.

Almost all the pleasure boats recorded capacity from 150 to 250 passengers, plus the service crew. There was a huge tiller at the rear, which the captain of the boat managed, and ladies and gentlemen’s cabins fore and aft respectively. On top of these was the promenade deck, provided with benches and ascended by stairs and surrounded by a rail. As there were many low bridges under which to pass during the trip to New Haven, people were constantly going up and down these stairs to allow passage of the boat.

By Marcia Helland

What shall we say of November? Gloom is her garment, and drab are her colors. Days dawn lead-en and stretch toward night as pewter mid-days deepen to charcoal by late afternoon. Ebony branches seem to clutch the slate skies sending our memories of their leafy boughs scurrying for shelter in the corners of our minds. The coppery leaves of autumn which floated silently from these same barren limbs now lie sere and crumpled, coated with the dust of the dying year. Yellowed corn stalks and bleached meadow grasses once green and undulant in the summer breeze pierce the hard brown earth like spears hurled in battle.

November is a time of endings. The year is on the wane. The brief daylight hours must be cherished, hoarded. Gentle breezes that brushed our sunburnt brows as we tended summer garden beds have turned to bluster and bravado. The wistful promise of spring, the seductive languor of summer, and, alas, even the bountiful product of autumn must be tucked away in that memory bank where we treasure the fragrance of violets, the chirping of spring peepers, the tickle of salt sea spray. The cello solos of bullfrogs, the taste of ripe plums and the smoke scent of bonfires.

No Need

To Fear

November

No Need

To Fear

November

Nov 1984

Sad, grey November, what can we say of you? Have you been the victim of bad pub-licity? The Saxons called you “wind-mon-ath”. You were dubbed the month of “blue devils and suicides”. Robert Burns wrote of your “surly blast”. Can we find some bright-ness, something redeemable in you? Let’s consider. . . .

The robins are gone, but you give us eve-ning grosbeaks. Larks and swallows have fled your heavy gales, but the hardy chicka-dee and his button-eyed cousin, the tufted titmouse continue their chattering and acro-batics at backyard feeding stations.

The baseball bats and tennis racquets have been stored away til spring, but you re-serve nearly all your thirty days for school-boy football and save one special day for tra-ditional arch-rivalries on high school fields.

Your palette is brown, tan and grey, but often you give it a dusting of pure white, and you promise us future days of sledding and snow forts and skating, and rosy cheeks to match the bright red mittens we’ll wear.

By Bernadette Gentry

The fields were harvested, the pumpkin pies have been baked in the oven, the tur-key roasts to a crisp, golden brown. Either in person or virtually we come together this day to give thanks for all the blessings in our lives.

It’s different this year for me, a dear friend has passed due to complications of the vi-rus, and others lost will be deeply missed.

Thanksgiving Thoughts

Thanksgiving Thoughts

With the holidays fast approaching, thoughts turn to festive meals. Along with the traditional turkey, Indian pudding and pump-kin pie, cranberries will adorn many a table this Thanksgiving and Christmas.

The small, tart, red cranberry used for sauce or jelly, is synonymous with Cape Cod, and a legendary tale explains why.

The tale narrates how, during an argument with the Reverend Richard Bourne, an Indian medicine man lost his temper and chanted a bog-rhyme, mired Bourne’s feet in quicksand.

by Carol Leonard

You embroider our windows with frost, your icy winds make our eyes water, and your pelting rains send fishermen ashore to beach their craft until calmer weather re-turns. But aren’t you just reminding us of what we must do? You tell us to make prepa-rations. Pile the logs by the back porch, put up the storm windows, drape an afghan over the back of the living room couch, air the scarves and mackinaws, oil and water-proof the winter boots, bake and store the fruitcakes, finish preserving the peaches and relishes, crack the walnuts, and hug our families close as we gather by our hearths on your raw, dusky evenings.

You remind us of our mortality, yet you give us time to reflect. You make us wistful for what we have lost, yet on one of your days we shall give thanks for all that we have.

Wise November, you are the open door to the festive gatherings and family traditions of the coming holidays. You are the bridge that takes us from the bounty autumn to the blessings of Christmas. You remind us, after all, that “to everything there is a season”. The rains of spring have cleansed us, the sum-mer sun has warmed us, and we know what to expect and how to make ready I think we need not dread November.

Southwick Cultural Council

Seeking Applications for Grants

The Southwick Cultural Council (SCC) for arts, humanities, and interpretive sciences, is now accepting grant applications on-line from individuals, organizations, and schools. Deadline for applications is NOVEMBER 16TH. The on-line applications can be completed and submitted at www.mass-culture.org. The application process is simple asking applicants for basic budget information and the scope of a project. According to Chair Su-san Kochanski, the Council is looking to gift $6500 in grants that support a variety of artistic projects and activities in Southwick including exhibits, festivals, short-term residences, or perfor-mances in schools, the public library, workshops and lectures. For more information contact Susan Kochanski at 413 569 0946.

Local Authors: Book News Release

Local author, poet, and musician Philip Pothier has published his collected woks in a new book, “Poems and Songs from the Heart”. The poems reflect insight into many years of country life in Granville, MA. They bring memory to the nostalgic country ways and activities of a by-gone era, many of which still survive today, that he learned from the old farmers in town. The song lyrics represent 50 years of loving and servicing the Lord. They present both joy and sorrow, but end with victory in Jesus! All come from the heart of the author to you! Both a book and cd containing eight of his own songs are available at Cooley and Company, 66 Granby Road in Granville, or from the author at 210 Sodom Street (please call in advance 357-6618) or online from the publisher covenantbooks.com

Friends of the Westfield Athenaeum

Star Lights Luminaria Fundraiser

Honor the stars in your life with luminaria this December, sponsored by the Friends of the Westfield Athenaeum. This is a wonderful opportunity to remember and honor family and friends and to recognize workers who are helping us get through these difficult times. Luminaria will be displayed in front of the Athenaeum and at other downtown locations on three Saturdays (December 5, 12, and 19) from 5 to 8 p.m., weather permitting. Each personalized luminaria is $6.00, and may be ordered on-line (Venmo and Google Pay accepted) or by sending in an order form and check (payable to FOTWA). Purchasers may pick up their luminaria to take home on De-cember 19 at 8 p.m. The deadline to order is November 7. See the Friends of the Westfield Athenaeum webpage for details and order forms (printed forms are also available at the circulation desk and Library To Go table at the Athenaeum): https://www.westath.org/friends-of-the-library.

COUNTRY PEDDLER

CLASSIFIEDS

GOODS & SERVICES

traprock driveways built & repaired. Gravel, loam, fill deliveries. Tractor services, equipment moved, York Rake. Bill Armstrong Trucking. 413-357-6407.

DELREO HOME IMPROVEMENT for all your exterior home improvement needs, ROOFING, SIDING, WINDOWS, DOORS, DECKS & GUTTERS extensive references, fully licensed & insured in MA & CT. Call Gary Delcamp 413-569-3733

RECORDS WANTED BY COLLECTOR - Rock & Roll, Country, Jazz of the 50’s and 60’s All speeds. Fair prices paid. No quantity too small or too large. Jerry 860-668-5783 or G.Crane@cox.net

GOODS & SERVICES

ST. JUDE’S NOVENA- May the sacred heart of Jesus be adored, glorified, loved and preserved throughout the world now, and forever. Sacred Heart of Jesus pray for us, St. Jude, worker of miracles pray for us. St. Jude, helper of the hopeless, pray for us. Say this prayer 9 times a day. By the 8th day your prayer will be answered. It has never been known to fail. Publication must be promised. Thank you St. Jude for granting my petition. -GR

ST. JUDE’S NOVENA- May the sacred heart of Jesus be adored, glorified, loved and preserved throughout the world now, and forever. Sacred Heart of Jesus pray for us, St. Jude, worker of miracles pray for us. St. Jude, helper of the hopeless, pray for us. Say this prayer 9 times a day. By the 8th day your prayer will be answered. It has never been known to fail. Publication must be promised. Thank you St. Jude for granting my petition. -SB

Some of us will have younger people, so-cially distant, deliver our dinners to us, and we will miss being together as a family. Still we know there is much to be thankful for - the Beauty of Nature that speaks of God, the creator, the birth of babies that shows life goes on, the joy our pets bring us, and caring acts of friends and family that keep us going.

Yes, even though times are difficult, it is still good to say a sincere thank you to all who make our lives better, by their work and thoughtful actions, especially those in the medical profession, those who work in stores and those who bring necessary deliveries to our homes.

May God Bless them all, and may God Bless our beloved country.

They then agreed to a contest of wits which lasted fifteen days, during which Bourne was kept from theory and starvation by a white dove which placed a succulent “cherry” in his mouth from time to time. Unable to cast a spell upon the dove, and exhausted from his own lack of food, the medicine man finally fell to the ground and Bourne was free. In the meantime one “cherry” brought by the dove had fallen into the bog and had grown and multiplied. Thus the cranberry came to Cape Cod, according to New England folklore. First Published Nov 1984

Here’s the good news: God loves you … wrinkles and all! God sees you just the way you are – wrinkles, warts, whatever – and He loves you just the way you are.

You say, “What about all my faults? All my mess ups? My mistakes? Surely God doesn’t like that.”

Well, take a look at that cross. Look at the cross of Christ and “think thanks.” All your sins have been taken away from you and put on that cross. Now God can say, “I have just one thing to say to you: ‘I love you and I will never, ever abandon you.’”

And so, let me ask you one final time … What tent are you going to live every day in, and sleep every night in? Content or Discontent? It’s your choice. Why not make up your mind to be happy?